Why aren't teacher salaries rising more?

Or, why teachers need better career pathways

Why aren’t teacher salaries rising more?

It’s not the total amount spent. In real, inflation-adjusted terms, overall education spending is up, especially in per-student terms.

Teacher benefit costs are rising rapidly, especially the cost of unfunded pension liabilities, but the amount of money that schools spend just on teacher salaries has also outpaced inflation.

So what is it? Why isn’t higher spending leading to higher salaries? One problem is that there are more people (more workers) in schools. A combination of state and district decisions to boost staffing levels has meant that more people are sharing the pie.

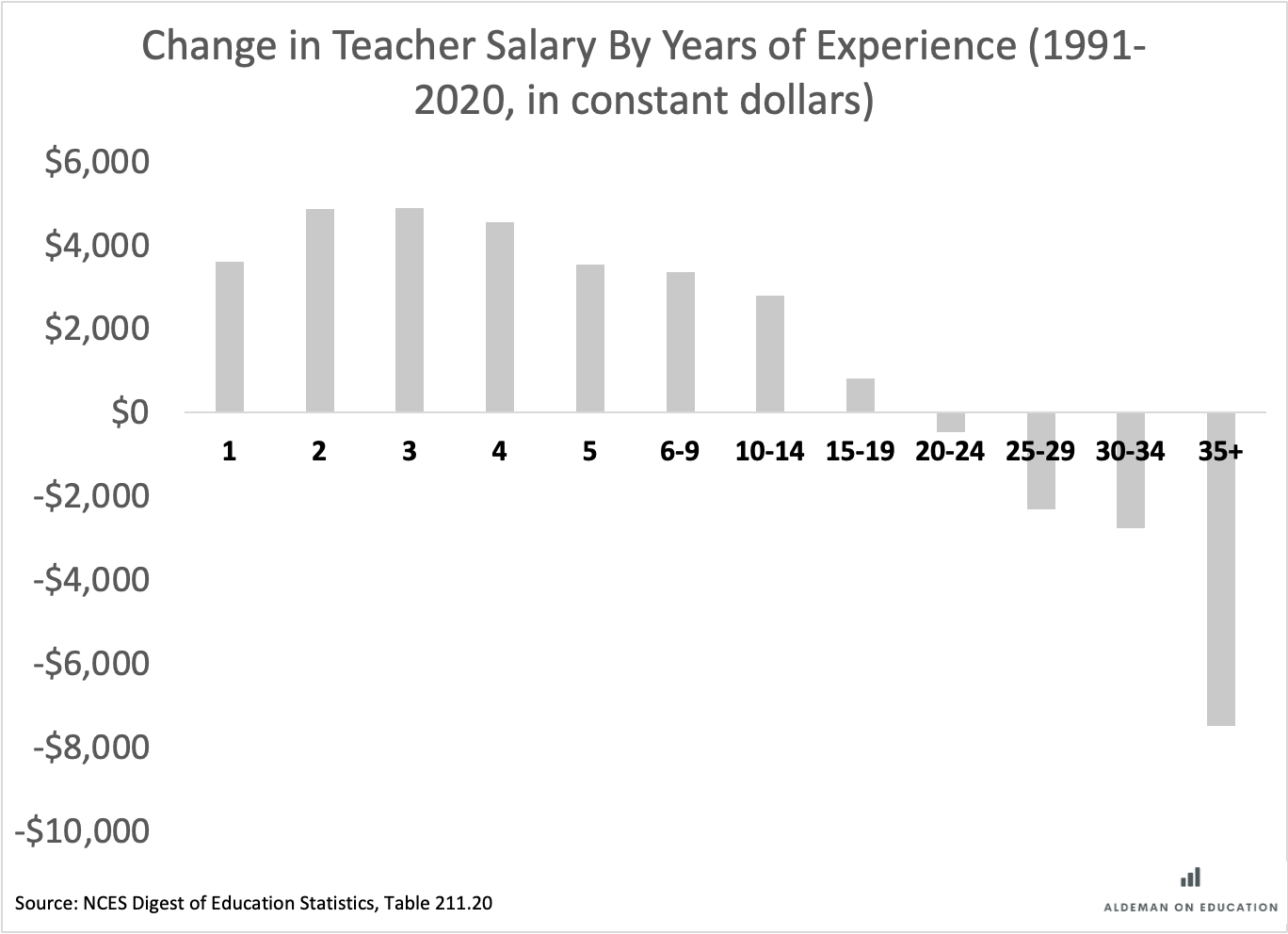

But today I’m going to look at one other factor. Namely, the convergence of teacher salaries over time. The chart below shows the change in teacher salaries from 1990 to 2020-21, broken down by years of experience. All the numbers have been adjusted for inflation to allow for comparisons across time. Among all teachers, the real, inflation-adjusted average salary rose $30 over this time period. Basically, it kept up with inflation and not much more.

But this average is masking some differences. Let’s start with the left side of the graph, which shows that real starting salaries and salaries for teachers in their first 19 years of service have all risen over time.

This shows up in other data as well. NCES conducts regular surveys of recent college graduates. The salaries of beginning teachers have always been a bit lower than in other fields, but that gap has stayed relatively consistent over time. In 1990, people who just graduated with a teaching degree earned 24% less than other recent college graduates. In 2016, the gap was slightly smaller, at 22%.

In other words, beginning teacher salaries are keeping up.

That’s not true for more experienced teachers. As you can see in the righthand side of the chart, the inflation-adjusted salaries of teachers with 20 or more years of experience has fallen. Now, remember these data are comparing snapshots in time and individual teachers advanced up the salary schedule and got cost-of-living raises over this time period.

The end result is that, nationally, teacher salaries have become more compressed.1

Are salaries in other fields becoming more compressed? No, not at all. In fact, wage inequality has gone up dramatically over time as pay for college-educated professionals has far outpaced the pay for non-college workers.

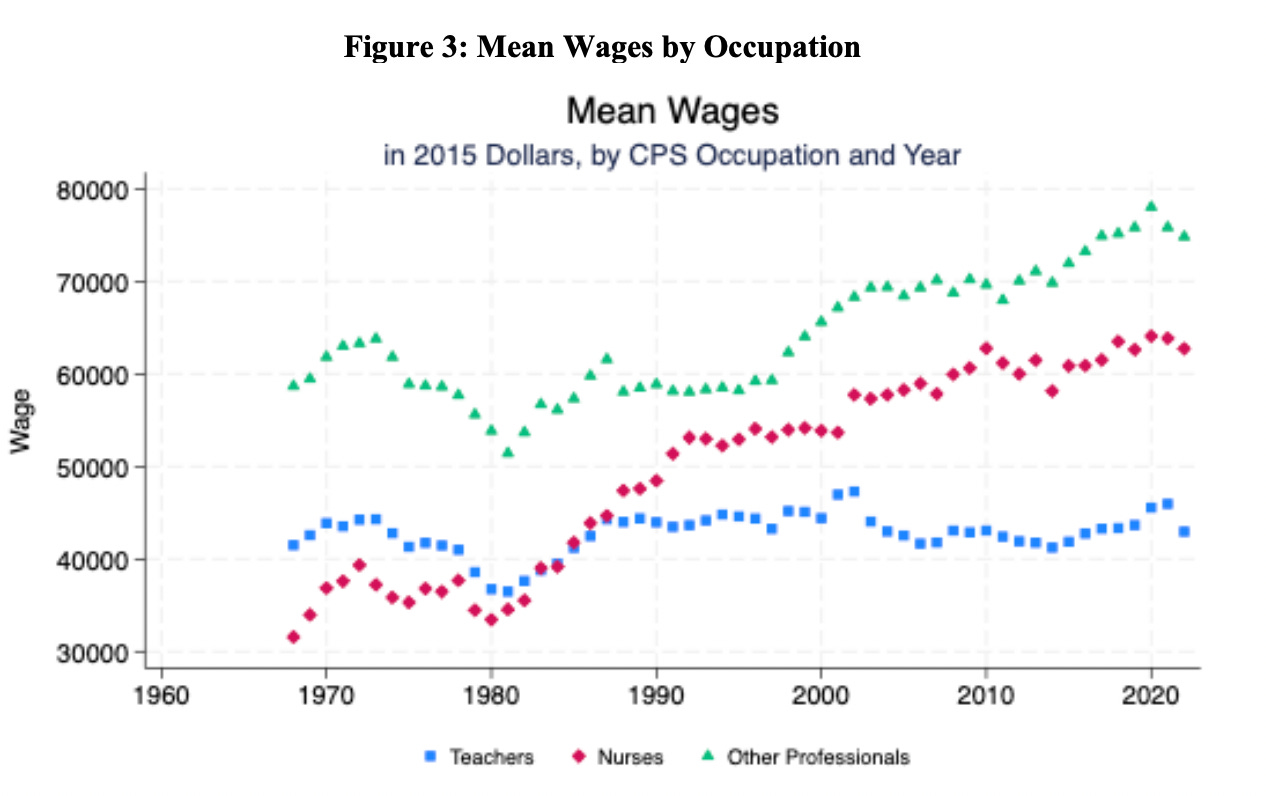

A recent paper by Shirin Hashim and Mary Laski suggests that these effects are making teacher salaries look worse, relative to other occupations. They compared the wages of teachers, nurses, and other “managerial and professional speciality occupations.” As you can see in their Figure 3 below, teachers (in blue) earned more than nurses did back in the 1970s (in red). But while teacher salaries merely kept up with inflation over time, the salaries of nurses have risen markedly.

What’s behind these trends? Hashim and Laski find that one explanation is this compression issue. While other professions, including nursing, have become less compressed over time, teacher salaries have not.

Another way to say this is that most professions compensate their highest-paid workers much more than their lowest-paid ones. That’s less true in teaching, and it’s at least part of the reason that veteran teacher salaries look so unfavorable compared to other well-educated professionals in other sectors.

Should schools try to solve the teacher salary compression problem? If so, how?

It’s not clear that compressed teacher salaries is entirely a bad thing. There was a concerted policy push 10-15 years to get districts to “front-load” their salary schedules and raise early career salaries. Jacob Vigdor pointed out that teacher salaries were particularly back-loaded compared to other professions. Josh Mcgee and Marcus Winters found that total compensation was even more back-loaded once you factored in teacher pension benefits. There may be positive benefits to recruitment efforts if districts are devoting a higher share of their budgets toward beginning teachers, especially in the form of higher starting salaries.

There are also different ways to increase or decrease salary compression. In education we’ve traditionally paid teachers largely based on their years of experience and credentials. Adjusting the ratio between the highest- and lowest-paid employees using traditional salary schedules would be perhaps the easiest way to do it, but it wouldn’t necessarily solve the actual problems at hand.

For example, the connection between pay and turnover is not as clear-cut as you might think. And teachers with Master’s degrees are no better than those without. As a cautionary tale, check out this Baltimore Banner piece about when a district rewards Master’s degrees without any oversight. The Baltimore City district discovered it was spending $1.9 million a year in bonuses to teachers who “earned” 60 course credits—the equivalent to two Master’s degrees—by completing online courses that required nothing more than some multiple choice tests. Teachers who “completed” these programs were boosting their pay by $15,000 to $20,000 a year. That policy increased salary dispersion, but it probably wasn’t a good use of money.

There are better ways to do this.

One way would be for districts to give Master’s degree pay but only for credentials that were directly tied to the teacher’s effectiveness in the classroom. The evidence is much stronger on the value of Master’s degrees in advanced math or science, for example.

Districts should also be much more willing to invest significantly more money in their best teachers. Teacher quality matters tremendously, and districts like Washington, DC and Dallas, Texas have had success with paying their best teachers a lot more money, especially if those teachers are willing to work in high-need schools and subjects.

States and districts should also be willing to invest more money in recruiting and retaining teachers in shortage areas. If it truly costs a district $20,000 whenever a teacher leaves, as The Learning Policy Institute found, then districts should be willing to pay similar dollar amounts to retain their most valued employees.

But perhaps the best way to raise teacher pay is to deploy teachers differently. Rather than using the traditional one-classroom, one-teacher staffing model, there are a growing numbers of schools that use team-based teaching staffing models. These models all start by identifying the most effective teachers in a school and giving them responsibility for leading teams of instructors. In exchange, these “master” teachers can earn significantly more money. In one model, called Opportunity Culture schools, these lead teachers can earn 20% more money.

Hashim and Laski might call these models an increase in teacher “productivity.” For instance, they note that in nursing a number of tasks have been streamlined, and there are greater financial rewards for higher-level specialization. Becoming a nurse anesthetist, for example, requires additional training and comes with increased responsibilities and higher pay.

From an education lens, team-based teaching models have the potential to raise teacher pay by fundamentally changing the role of teachers and creating specialized roles in the service of improved student outcomes.

There are probably some composition effects at play in these national averages, as lower-paying states in the South and Southwest grow and the higher-paying states in the Northeast shrink.

I would also look at the practice, big in the 90s, of compacting steps on teacher pay scales. When I started, there were 35 steps on the district pay scale; that was whittled down to around 14. The idea was to improve career earnings for teachers, but it also made districts reluctant to create larger steps in the salary ladder, effectively freezing the distance between bottom and top steps.

Thank you for this, Chad. As always appreciate your willingness to dig into nuance here. On the 20+ years of experience side of things, I wonder how much of that is driven by salary schedules in some states capping growth beyond a certain number of years. For example, in Georgia, once a teacher reaches 21 years, there are no more years of experience gains in the state schedule that drives the funding formula (most districts have flexibility to pay more if they want but the state formula pays the same regardless). In North Carolina, it’s 15 years. By that time, teachers may not have more degrees or certifications to gain to continue getting increases, so their salary stays flat (and negative in real terms). I’m not sure how common this is in other states but thought I’d mention here. Thanks again!