The State Assessment Game of Telephone

Too many states are putting parents last

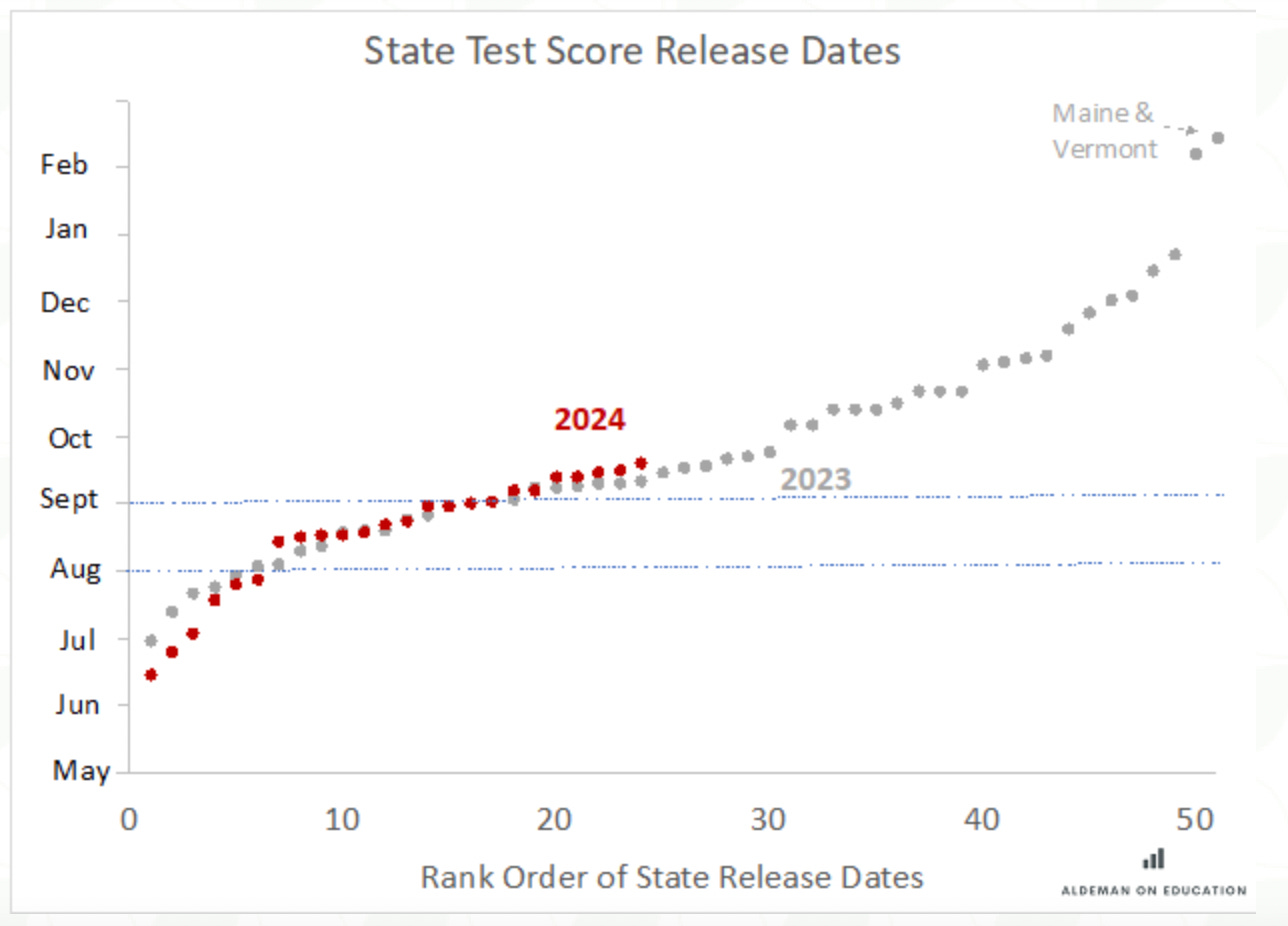

Last week I wrote about how slow states are to release results from their annual Spring assessments. Here we are in pumpkin spice / decorative gourd season, and half the states still have not released their results yet.

To put it colloquially, this is too damn slow! Summer is the key here—it’s the time when parents and educators could actually do something about the results. By the time Fall rolls around, kids are already back in school and they’ve moved on to the next grade. Teachers have already written their lesson plans for the year.

But today I want to elevate one of the points I made in my piece for EduProgress.org. Namely, when it comes to releasing their results, too many states are putting parents last. Instead of giving the information to parents right away, they’re often following a sequence more like this:

Wait for every single kid in every single grade to finish every single test;

Give kids a chance for re-takes;

Send preliminary results to school districts, to confirm which kids go to which schools and are in what grades;

Draft a formal release, and share messaging with key stakeholders (governors, legislators, district administrators);

Release the state, district, and school results to the public; and then,

Rely on individual teachers and administrators to give results to parents.

This game of telephone slows down the reporting process and dilutes one of the key purposes of state assessment systems. State tests are meant to provide parents with an objective check on how their child is doing. They are supposed to help parents know if Johnny is learning to read with comprehension and if Susie is on track for algebra.

This game of telephone is also unnecessary in today’s modern world. Most state assessments are now administered on computers and can be scored instantaneously. Private testing companies like the ACT and SAT promise to deliver results in 2-4 weeks. (The test makers say it may take another week or two to score written tasks.) Heck, I’m dating myself, but when I took the GRE test online back in 2006, I received my preliminary score literally seconds after I finished. They sent me written confirmation a few weeks later.

States should be doing the same thing with their annual assessment results. They should be sending at least high-level, preliminary results back to parents within days of when the child finishes his or her test.

If the technology exists, why aren’t states doing it? It could be inertia, and this back-and-forth was how it was done back when the tests had to be administered with paper and pencil and hand-scored. Other people have insinuated there’s a political motive at play, and state departments are trying to control information. Or, it could be that state departments of education are compliance-oriented and don’t see parents as their primary clients.

Some people have insinuated it takes this long because state tests are “high-stakes.” I have to call b.s. on this one. The ACT, SAT, and GRE all have much higher stakes attached than the typical state assessment, and they somehow manage to return results faster.

And that’s the sad reality. Most state tests have no formal consequences attached to them. Take my family as an example. My daughter is in 7th grade this year, and we live in Virginia. So far she has completed the following state tests:

A reading and math test in 3rd grade;

A reading and math test in 4th grade;

Reading, math, and science tests in 5th grade; and

Reading and math tests in 6th grade

Out of these nine tests, exactly one of them had any sort of stake attached to it. As I wrote previously, our district used her 6th grade state math test to determine what math class she should take in 7th grade. But that was all upside for her—there was no penalty if she had not done well on the test.

That means 8/9 of the tests she’s taken so far had no consequence for her or any other student who took them.

Looking ahead, Virginia does have some higher-stakes tests for high schoolers, who are required to complete a certain number of courses in each subject and to take (and pass) state exams in those subjects. Looking outside Virginia, there are some states that require 3rd graders to demonstrate they can read proficiently before advancing to 4th grade.1 If anything, these states tend to return their results much faster!

Ok, ok, you might say, what about the fact that the results of these tests feed into school accountability systems? Didn’t No Child Left Behind say that states could take over or close a low-performing school if its test results didn’t improve? Aren’t those high stakes? Yes, that is technically true, but when I tallied it up back in 2019, I found 65 news stories about the threat of potential consequences for every 1 school that actually faced them. I used to call this “faux accountability.”

But let’s set that aside. There’s actually an easy way to square this circle. States could put parents first on their lists. No more game of telephone where parents are the last ones to find out about their own child.

States could give parents preliminary results and take their time before releasing the final results to the public. This is what Ohio did. Last year, they passed a new rule providing parents their child’s state exam results no later than June 30th of each year. Virginia did something similar. I saw my children’s results at the end of the school year last Spring. Parents in other states are still waiting…

This post is not attempting to evaluate the effectiveness of those mandates. Some studies have found the mandates can be imposed arbitrarily across racial and economic lines, but other studies have found some promising academic gains both for students who are held back and even for their younger siblings.