The returns to education are linear (mostly)

Missing a day of school is bad; missing 10 days of school is 10x as bad

Sometimes in education we get hung up on benchmarks and milestones. But it’s important to remember that the value of education is mostly linear.

What do I mean by that? Well, there’s a lot of research that people with more education get paid more money. Well-educated plumbers and retail sales managers end up making more money than plumbers and retail sales managers with less education.

There absolutely is some signaling value of education, especially at the college level. Some employers won’t really care about your college major or even the specific college you attended, but the fact that you got in, stuck around, and made it through sends a signal to future employers about your talent and perseverance.

But education is also not purely about the signaling value of the highest diploma you happen to hold. As Harry Patrinos has documented, the returns to an extra year of schooling are large and fairly consistent across the world. In Sub-Saharan Africa, an extra year of schooling is worth an earnings bump of about 12 percent; in North America, it’s closer to 9 percent. Investing in yourself tends to pay off.

There’s some interesting work here in the U.S. about how much education pays and why it doesn’t seem to provide the same return to all students and all types of education programs. Those are important areas to research, but today I want to re-focus on the averages. To make my point, I’m going to focus on two examples: attendance and tutoring.

Let’s start with attendance. Here in the U.S. policymakers have tended to focus on the rates of chronic absenteeism, or the percentage of kids who miss 10% or more of the school year. That works out to missing 18 days out of an 180-day school year, or about two absences per month for a nine-month school year. This is an important and useful benchmark, and there’s research suggesting that kids who miss this much time are less likely to succeed academically and to stay on track and graduate.

But we also shouldn’t become enamored with the hard cut-off. Other than a technical counting exercise, nothing happens when a kid misses their 18th day of school versus a kid who “only” misses 17 days. Both students are in danger of missing out on key instructional time and falling behind.

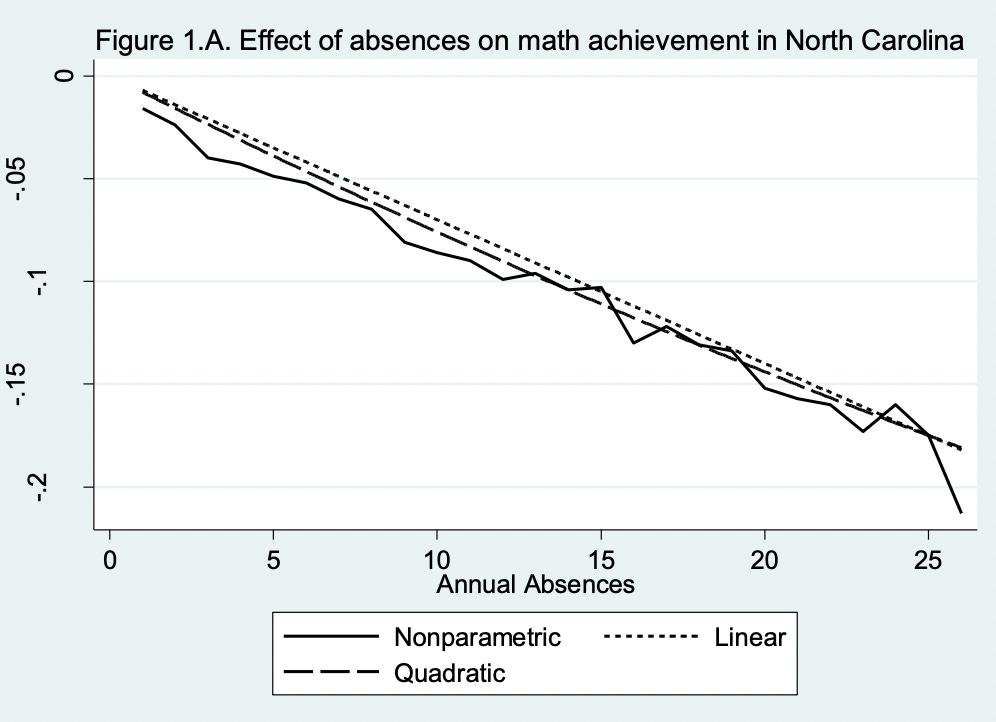

I’ve found that people often misunderstand this. They fear that absences snowball, and that the effects grow exponentially. But that’s not right. In a 2015 paper, Seth Gershenson, Alison Jacknowitz, and Andrew Brannegan looked at the effect of absences on achievement in North Carolina. They found that it actually looked more like a linear trend. An absence was bad, and 10 absences was ten times as bad. As you can see in their chart below, for math, there’s nothing magical about the 10% chronic absenteeism threshold. They found a similar linear relationship in reading.

At a research discussion in May hosted by AEI, Gershenson presented data from North Carolina and Maryland suggesting that a similar linear relationship continued to hold post-COVID.1 In other words, we wouldn’t want schools to pat themselves on the back if all their kids missed “only” 17 days of school or to give up on students who already passed the threshold for chronic absences.

This is actually good news, and it sends a clear message to teachers and school leaders: Attendance is important, and every day matters. The more days that kids can attend school, the better.

As other panelists at the AEI event noted, state and district policymakers can learn a lot by studying their data and acting on early information. For example, students who miss a lot of days in September and October likely need quick interventions to get back on track.

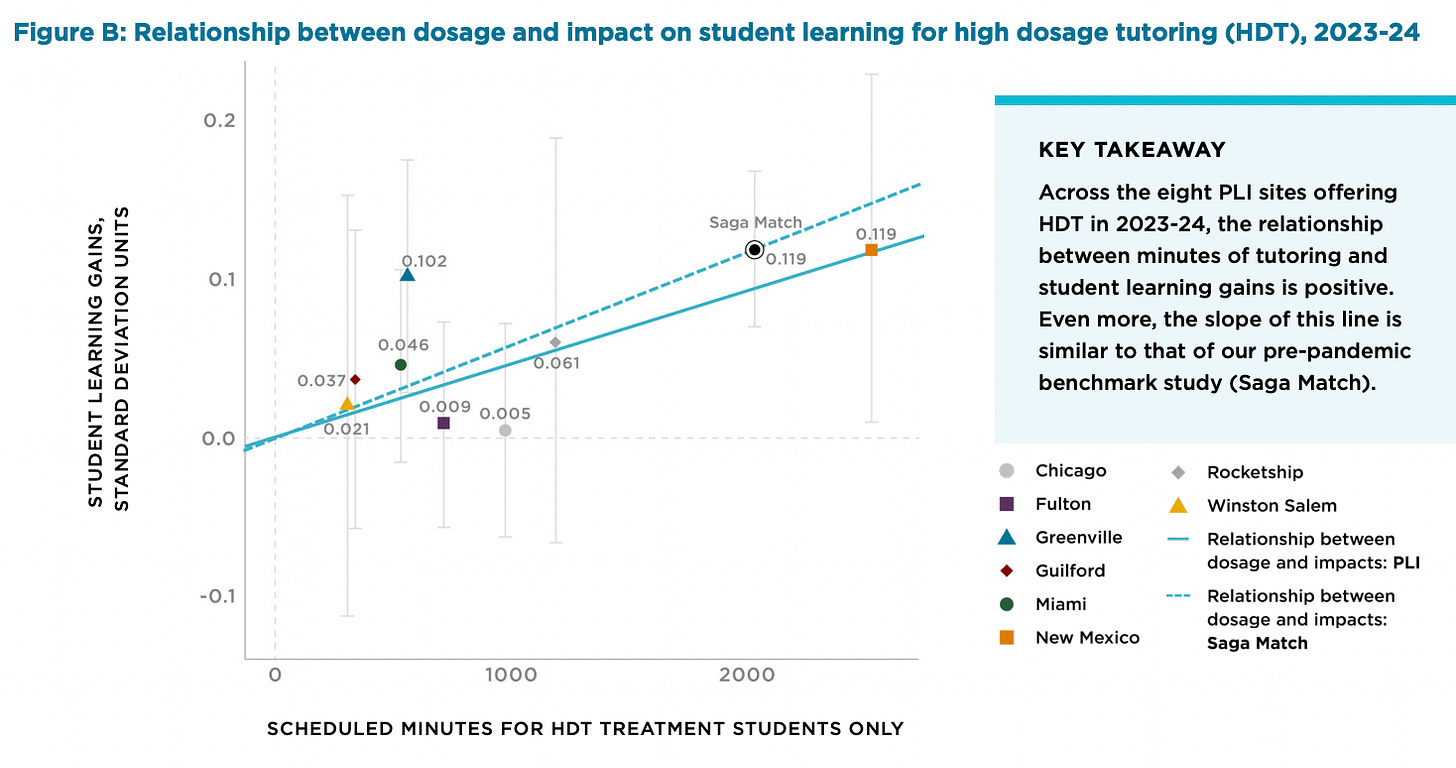

Which brings me to tutoring. Here, too, the message is pretty clear that the dosage and the amount of tutoring that a student receives matters a great deal. A new report from MDRC dives into tutoring programs in the 2023-24 school year from a variety of settings using a range of delivery mechanisms. They found that, “When benchmarked to prior studies conducted on Saga Education’s high dosage tutoring models, the amount of learning per minute of tutoring seems similar, for the most part, even as these practitioners adapted it to their different settings—urban, rural, or suburban districts; delivered virtually or in person; and using different group sizes.”

This key takeaway is captured in Figure B from their report, reproduced below. Each dot represents a different tutoring model or location, and the solid blue line shows the relationship between the number of minutes of tutoring that students were scheduled to receive versus the academic effects of that tutoring. The line points upward and to the right, meaning that students who received more tutoring saw larger gains.

Now, you could take the Debbie Downer view of these results. Most of the individual tutoring programs had large variations across students and many were not statistically significant. Or, you could point out, as Jill Barshay did for Hechinger, that logistical challenges meant these programs weren’t able to deliver much tutoring time for students. There are implementation challenges, to be sure.

But here too there’s a clear and positive message: Tutoring can and likely will boost student learning outcomes, but it’s all about the dosage and the amount of time that students actually spend with their tutors. The same finding shows up in research on student learning apps like Khan Academy and Zearn, on other forms of math homework, and on summer school programs. In all of these, a bigger dosage equaled bigger gains. In my summary of this last year, I noted that getting students to spend more time on task is the key to boosting student learning outcomes.

In general, more time learning = more learning gains for students.

The new data did seem to show that one individual absence was slightly less-bad in the post-COVID world. That could be due to more technological work-arounds like Zoom or the ability for students to complete homework remotely. This is an interesting finding, but the main result continued to suggest that individual absences were harmful and they affected students in a relatively linear fashion.

On target, NYC is deeply engaged in what they call attendance compliance, software that tracks attendance daily, school compliance attendance plans, coordinating with social service agencies, they need an external examination of whether their efforts have improved attendance and the academic impact, of course, NYC has a few other issues 🤒