Odds and ends...

Fertility rates, Social Security, FAFSA, and more...

I’ve been buried in some big data projects for The 74 and other clients (more on those soon!), but I wanted to share a few data-driven stories that caught my eye recently. From falling birth rates to reading progress and teacher pay, these snapshots reflect big shifts happening quietly—and not so quietly—beneath the surface.

Birth rates continue to plummet worldwide

I’m late to this one, but this Financial Times piece on “peak population” from John Burn-Murdoch is really striking. It turns out that government agencies keep projecting that birth rates are going to stabilize at some point, or at least slow their rate of decline, and they just… aren’t.

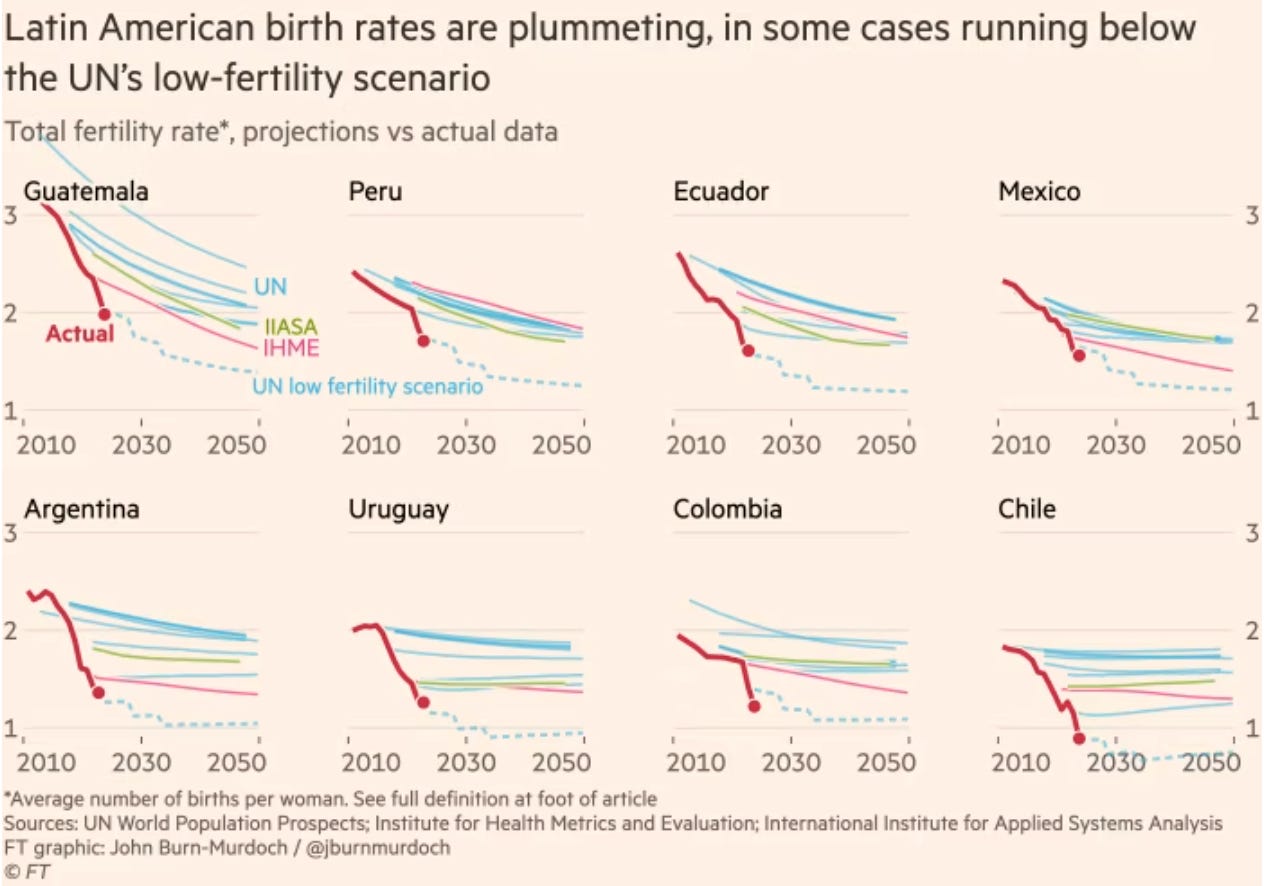

You can see this for Latin America in the chart below. Did you know, for example, that Mexico’s total fertility rate is now below that of the United States?

The projections, in the lighter shades of blue, green, and pink, all show declines. But the actual birth rates, in dark red, keep coming in well below the predictions.

Here in the U.S., we have our own problems. On the education side, we see the same trends in the official school enrollment projections. The statisticians know the birth rates are trending downward, but they keep being overly optimistic in their future projections.

This is issue is also playing out at the Social Security Administration. The Boston College Center for Retirement Research points out that Social Security is assuming that fertility rates in this country will rebound from their current levels, of 1.63 per adult female, to 1.9. That assumption is higher than what the Congressional Budget Office and the Census Bureau use, and it ignores the trajectory of recent trends. Moreover, assuming a higher fertility rate makes it look like the Social Security program is in better financial shape than it really is.

Right now, if no action is taken, the Social Security Administration will need to cut benefits by 23% starting in the year 2033. That clock is ticking. And speaking of Social Security…

That teacher windfall is costing you

Last year I wrote about the Social Security Fairness Act. Contra the law’s misleading title, I showed how it would give relatively well-off teachers and other public servants in specific states a Social Security windfall. Moreover, the law speeds up the date at which the Social Security Trust Fund runs out of money and when we’ll have to start cutting benefits.

Well, the latest Social Security Trustees report has another way to look at it. They ran the numbers and found that, "The overall effect of [Social Security Fairness Act] is a decrease in the OASDI actuarial balance of 0.14 percent of taxable payroll."

What does that mean? Well, it’s effectively saying that Congress would need to increase the payroll tax rate by 0.14 percentage points, from its current 12.4% to 12.54%. To be truly cost-neutral, that change would have to occur immediately and stay in place permanently.

Or, to look at it another way, the national average wage this year is $72,256. (That’s very close to the average teacher salary, according to the NEA.) For the typical worker (or teacher), a tax increase of 0.0014 percent translates into an extra $101 per year.

That may or may not sound like much. But that $101 extra would need to be paid by 185 million workers. Meanwhile, the new windfall will increase benefits for about 2.8 million individuals who already have some of the most generous pensions in the country and who are at practically zero risk of poverty in old age. That doesn’t sound very “fair” to me!

Houston’s dramatic reforms are producing dramatic gains

Last month for The 74 I wrote about the “portfolio” model and the value in closing low-performing schools and expanding high-performing ones. That’s easier said than done(!), but I cited evidence from Florida, New Orleans, Indianapolis, and Denver about how those places have used this formula to great success.

Part of the reason for the need for the portfolio model is that it’s extremely difficult to turn around low-performing schools and districts. It takes a dramatic change in instruction to drive dramatic changes in student performance.

It is possible though, and one of the places I pointed to was Houston. Well, the latest Texas results are out now, and Houston’s reforms look even better. What has been at times a painful process is producing some dramatic gains. Check out Kevin Mahnken’s interview with Houston Superintendent Mike Miles on how they’ve done it.

Speaking of Texas…

Texas rewards great teaching

In my latest piece for The 74, I look at the Texas Teacher Incentive Allotment program:

Districts must use a validated observation rubric and evaluate educators at least annually. Under state guidelines, a “Master” teacher would perform at about the 95th percentile, an “Exemplary” teacher between the 80th and 95th percentiles and a “Recognized” teacher at the 67th percentile or above.

After the state verifies a district’s evaluation process, it starts sending out real money. Each Recognized teacher earns at least $3,000 for his or her school, with higher amounts for Exemplary and Master teachers. Extra funding is awarded if the teacher works in a high-need or rural school. For example, a Master teacher in such a school could bring in an extra $32,000 a year.

I argue that the Incentive Allotment program is a model for other states that are looking to identify great teachers and give them extra money for staying in the classroom. Read it here.

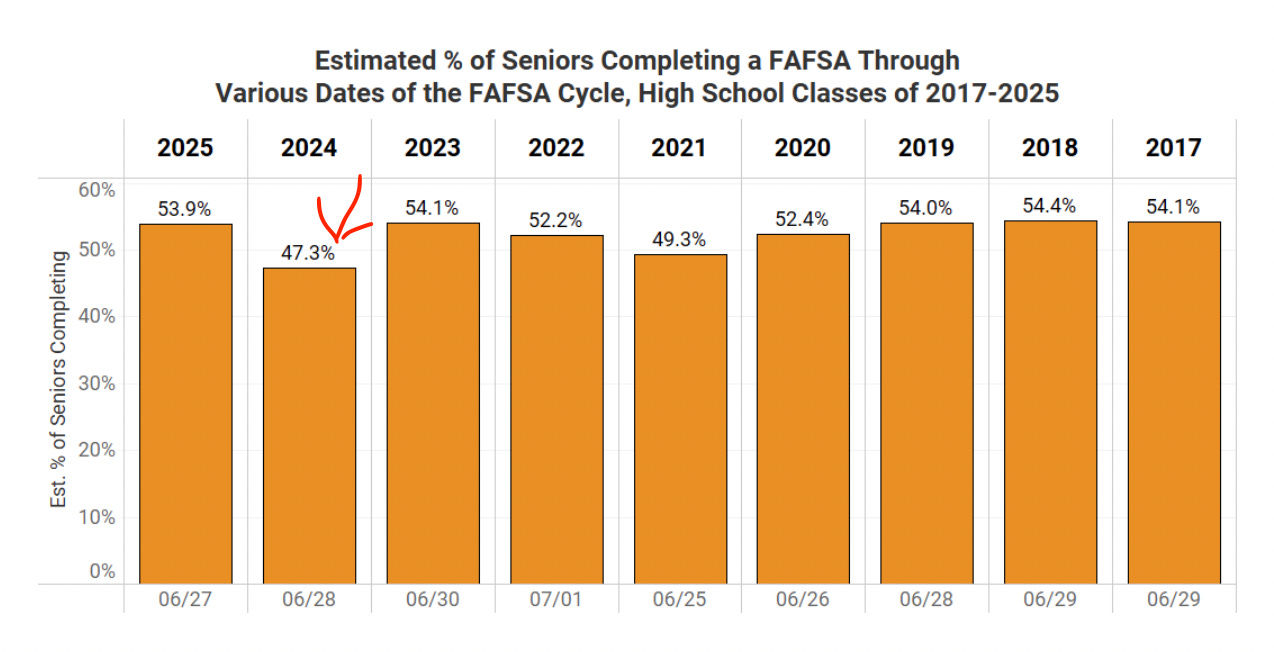

FAFSA completion rates have recovered

After the 2024 FAFSA fiasco, NCAN reports that FAFSA completion rates have now rebounded. Still, that means about 250,000 fewer high school seniors completed the FAFSA last year compared to a “normal” year.

While this year’s news is positive, I hope someone will follow up about what happened to all those “missing” FAFSAs last year…

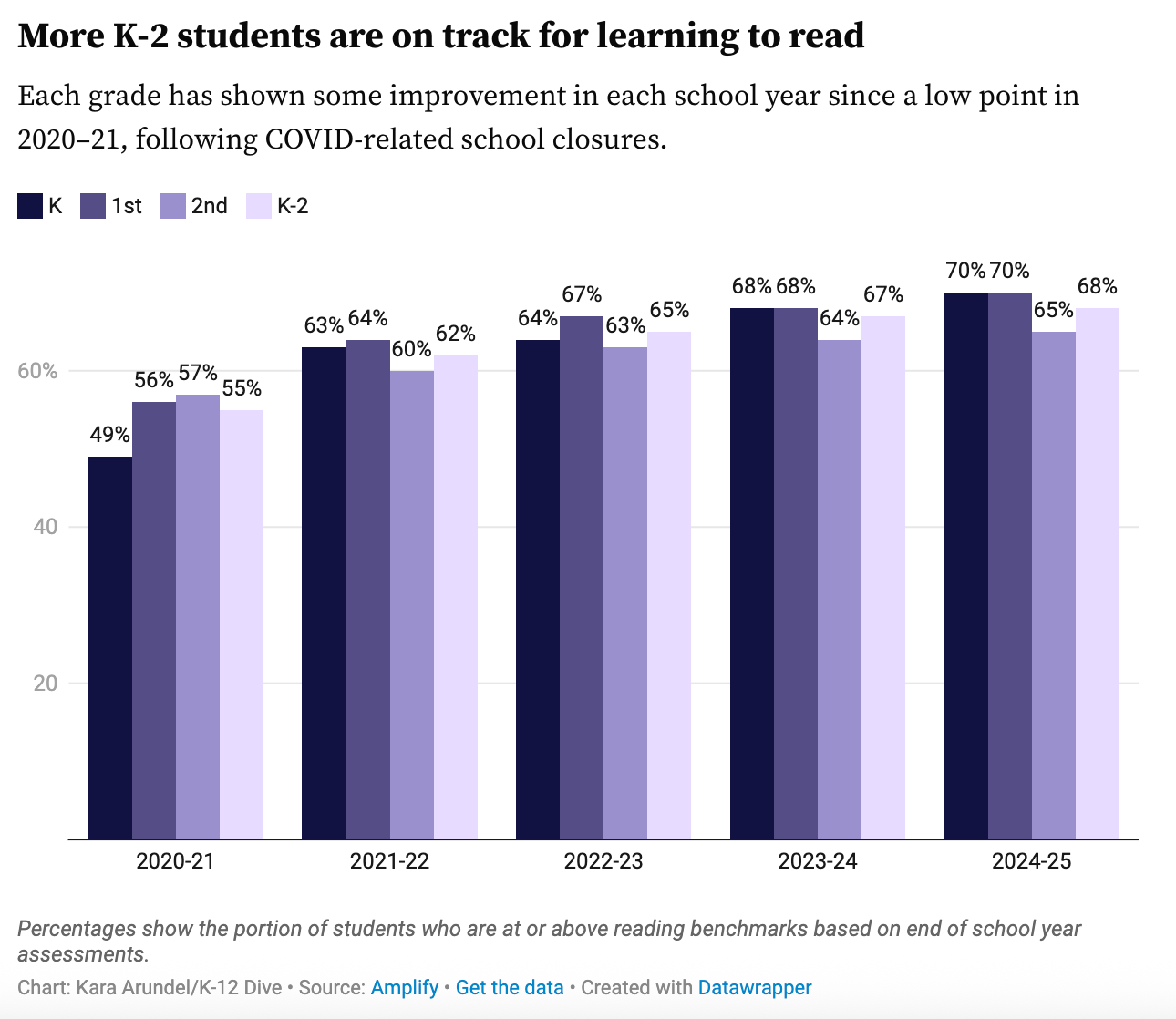

Reading progress, with a caveat

According to a story earlier this month from K-12 Dive, “Data from the end of the 2024-25 school year show 70% of kindergartners were at or above reading benchmarks. That’s up from 68% in 2023-24 and 49% in 2020-21.” Here’s the key chart:

Here’s the full report from Amplify.

This is great news, and worthy of celebration. But we should be cautious about assuming these gains in basic reading skills will automatically translate into improvements on tests of reading comprehension. That’s because most state tests aren’t designed to capture decoding ability, and they treat reading comprehension as a separate, isolated skill apart from the student’s background knowledge. As Miah Daughtery and I write in a new brief for HMH, “low comprehension can result from several factors, including poor decoding skills, weak reading fluency, or a limited vocabulary.”

In other words, states and districts should consider breaking apart their reading tests. They should focus on phonics and other basic skills in the early years, and then focus more on specific content knowledge (in literature, history, science, etc.), as well as writing, in later elementary and middle grades.

Writing is thinking

Nature has a short new piece explaining why, “Writing is thinking.” In an era where people are questioning whether kids actually need to learn how to write when they can just prompt ChatGPT, the authors note that:

Writing compels us to think — not in the chaotic, non-linear way our minds typically wander, but in a structured, intentional manner. By writing it down, we can sort years of research, data and analysis into an actual story, thereby identifying our main message and the influence of our work.

Over at No More Marking, Daisy Christodolou takes the argument in a different direction:

Often, we assume the main purpose of writing is communication, as though it works like this: I have a series of well-worked out and complete thoughts in my head; I write them down; other people can read them.

That is certainly one way we use writing, and the one that generative AI is perhaps best placed to help with. If you have a series of thoughts in your head, you can speak them into a voice memo and get AI to polish them up into a perfect paragraph or series of paragraphs. A good example is where you have a relatively simple decision to make - perhaps whether to say yes to an invitation or not - you make the decision, and then you struggle to communicate it. Generative AI can be helpful in these cases.

But there is another important function of writing which generative AI is less well placed to help with: writing helps extend working memory and is a tool for thinking. A lot of the time we don’t have complete and well-worked out thoughts in our head. It is only by writing our thoughts down that we discover the gaps and the flaws in them.

Good writing takes mental effort, and it is through that mental effort that we gain knowledge and organize our thoughts.

Do more of these "Odds and Ends," Chad! This was an excellent, informative lead that's given me about four more things to read. More, more, more!

It turns out that TFR is not what it sounds like it would be: it is _not_ the average number of children that women are currently having.

Rather, it is "the average number of children a woman would have in her lifetime if she were to experience the current age-specific fertility rates." Note the "if" which turns out to matter in a lot of developed nations.

In a society where there's been a shift underway in the ages at which women choose to have children, TFR stops being an accurate measure of real-life childbearing. The actual number of children birthed by actual women will be greater than the TFR number, and can become significantly greater.

For instance in the USA the TFR has been sliding downward for years and as of 2024 was at about 1.6; but the actual "children ever born" for U.S. women has since 2010 been higher than the TFR. As of 2024 that rate of actual births was at 2.0 and had been _rising_ for each of the past two years.

Several top demographers have recently begun writing about this misunderstanding, I'll link one of them below here.

Whether this applies currently to Latin American nations, I have no idea -- are women in those societies pushing child-bearing later in their lifetimes? Have teen births been declining there?

If yes to both of those questions, then the TFR is not a good indicator of current population trends in those places.

https://jenndowd.substack.com/p/is-our-population-collapsing