The Social Security "Fairness" Act Was A Lie

It will give windfalls to certain state and local government employees who don't pay into Social Security for parts of their career

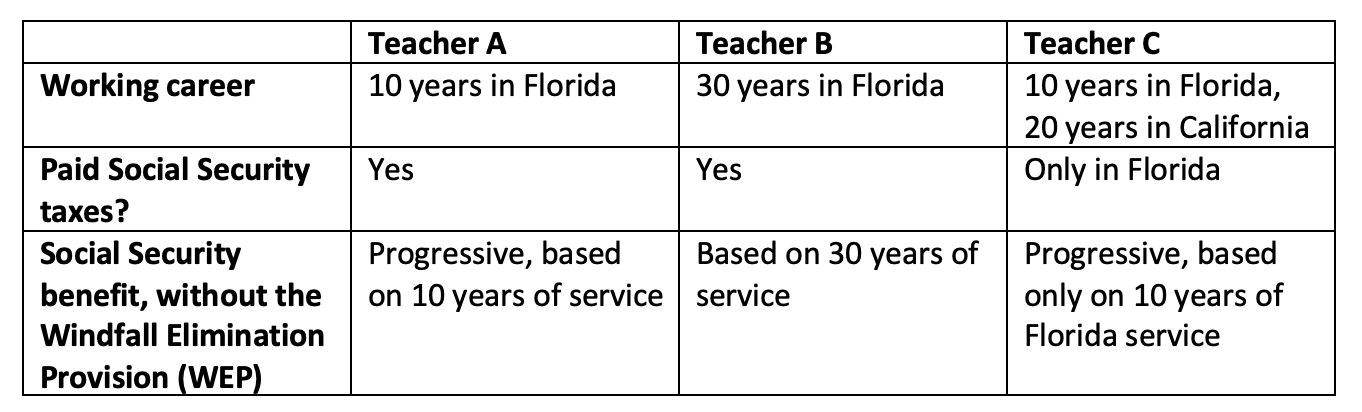

Consider three hypothetical teachers. They all start their careers working in Florida public schools. Because Florida participates in Social Security, they will all pay Social Security taxes while they work in Florida.

Let’s say Teacher A only teachers for 10 years. After that, she leaves to start a family.

And then there’s Teacher B. She works a longer career in Florida, again paying into Social Security the entire time.

Both of these teachers will receive Social Security benefits based on their entire working history. Teacher B’s benefit will be higher in absolute terms, because she worked for more years and contributed more into the system. However, Teacher A will actually get a higher return on her contributions, because Social Security is progressive and provides more generous benefits to lower-income workers.

But now consider Teacher C. She splits her career, first in Florida for 10 years and then in California for 20 more years. She will pay Social Security taxes for the Florida part of her career but not while she works in California, where public school teachers do not participate. When she goes to retire, her Social Security benefit will be tied only to her years in Florida. Moreover, because the Social Security program only knows about her time in Florida, she will get the same generous treatment as Teacher A.

Is this fair? Should Social Security award the exact same benefit to Teacher A and Teacher C?

Back in the 1980s, Congress said no. They said it wasn’t fair to ignore part of Teacher C’s work history, years in which she avoided paying Social Security taxes while accumulating state-provided retirement benefits. They created something called the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) to direct Social Security benefits to the workers who truly needed it more, like our hypothetical Teacher A.

Congress also applied similar rules to people who had a government pension but whose spouses did not (called the Government Pension Offset, or GPO). As the American Enterprise Institute’s Andrew Biggs explained in a recent piece, this provision ensured that people who avoided paying Social Security taxes (while accumulating pension benefits) weren’t treated to the same generous Social Security spousal benefits as people who did not.

After these provisions were enacted, the Social Security Administration began asking retirees to report any government pension they accrued outside of their Social Security years, and it reduced their benefits accordingly. The extent of the reduction depended on the number of years they contributed to Social Security, with people who were in line for more of a windfall facing a slightly larger penalty. They also included protections for people who had only a very small government pension—many of the workers with split careers ended up facing no penalty at all.

You can start to see who would be upset about these penalties—former state and local government workers, and their spouses, who had a sufficiently large pension benefit. They lobbied for years to repeal the WEP and GPO, and they finally persuaded enough congressional members to pass the bill late last year.

I wrote about this effort recently for The 74. I concluded that, “While union leaders are cheering the bill as a win for their members, it’s a bad deal for the rest of us. It will undermine the progressive nature of the Social Security program, cost taxpayers billions and force painful cuts down the road.”

Since I wrote the piece, I’ve received a number of emails claiming that they “earned” the generous treatment under the Social Security program. I disagree! And in fact, the people writing me often seem to have some misconceptions about how WEP worked. Here are three big misconceptions:

1. The WEP never applied to ALL state and local government workers.

This is a big one. Remember the hypothetical teachers above? Teachers A and B never faced a WEP penalty, because they contributed to Social Security their entire careers. If Teacher A had found another job in the private sector, she still wouldn’t have faced a WEP penalty, for the same reason.

In fact, it was only Teacher C, who spent many years working in a government job that wasn’t covered by Social Security, who was at risk of paying WEP.

By repealing WEP (and GPO) Congress will now treat teachers very differently depending on which state they happen to work in. As you can see in the map below, which I helped create for TeacherPensions.org, most teachers pay into Social Security.

Approximately 60 percent of all public school teachers—like our hypothetical Florida teachers—and 75 percent of all state and local government workers pay into Social Security and were unaffected by these two provisions. The only people who were potentially affected by the WEP and GPO rules were former federal, state, and local government workers who weren’t contributing to Social Security. In the education world, that’s the dark blue states on the map.

2. The WEP only hit workers with substantial pension benefits from their non-covered employment.

As I mentioned above, the WEP rules included protections for people who had only a very small government pension. This meant that if someone taught in California for only a few years, and then went into private sector employment for the rest of their career, they wouldn’t have faced a WEP penalty.

This turned out to be a pretty big exemption. When I ran some hypothetical numbers, I found that someone would have had to teach for 15-25 years in a non-covered position before they would have faced a WEP penalty.

As I wrote in this piece, the Social Security Administration looked at their data in 2019. They found 19.6 million total retirees who had ever worked a portion of their careers in non-covered state and local government positions. That’s a lot of people. However, thanks to the minimum protections I mentioned, 18 million of those workers (92%) faced no penalty at all.

Another way to say this is that only 8% of people who ever worked in a non-covered role had a big enough pension to qualify for the WEP penalty. These people may not be rich, but they’re not exactly poor either. By repealing the WEP and GPO, Congress just decided to treat them as if they were truly poor. In the process, they weakened the Social Security program that many low-income people really do rely on. That’s not good policy in my book.

3. Repealing the WEP does nothing to help the neediest workers.

The state and local government workers who need the most federal help are low-income, short-term workers who lack Social Security benefits. Let me explain.

When states were deciding whether to join Social Security or not—they had the choice starting in the 1950s—many decided not to in the belief that they could offer better benefits through their pension plans. That bet works out for full-career veterans. For those workers, state pension plans tend to offer pretty generous benefits.

But, as I and many others have documented, state teacher pension plans really only benefit workers who stick around for 20 or more years. If you leave before those cut-offs, you might qualify for some pension, but it won’t be worth very much. For all of those workers—and it’s the VAST majority—they would be better off if they were covered by Social Security.

And this is what makes me the most frustrated. Repealing the WEP and GPO was a missed opportunity to help everyone. Because, if Congress had voted to extend Social Security benefits to all the state and local government workers who currently lack it, they would have killed two birds with one stone. They would have provided retirement benefits to millions of workers who currently lack it, and they also would have eliminated the need for provisions like the WEP and GPO going forward. After all, if everyone is in the system and paying the same taxes, there would be no need for special treatments.

My only solace is that there will now be a much stronger case for universal Social Security coverage going forward. Not only is Social Security $196 billion closer to bankruptcy than it was before the vote—thanks to the higher payments, Social Security will run out of money faster—but the potential windfalls from working in a non-covered position will become more apparent. Eventually, that could spur a backlash and end the unequal situation we’re living in now.