Americans Are Stuck

We've stopped moving houses and jobs, and why that matters for education; plus school spending, studies of universal basic income, and "equitable" grading

Earlier this year I had the pleasure of reading Yoni Applebaum’s book Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity. He tells good stories, and I particularly appreciated the way he dug up housing records to tell the history of individual properties, the people who lived there, and how neighborhoods change over time.1

Applebaum’s key point is that Americans are moving a lot less than they used to. Whether that’s due to economic factors or a matter of personal choice, it means that people are less likely to move toward opportunity like their grandparents did before them.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal looked into why Americans seem to be stuck in place:

People are moving to new homes and new cities at around the lowest rate on record. Companies have fewer roles for entry-level workers trying to launch their lives. Workers who do have jobs are hanging on to them. Economists worry the phenomenon is putting some of the country’s trademark dynamism at risk.

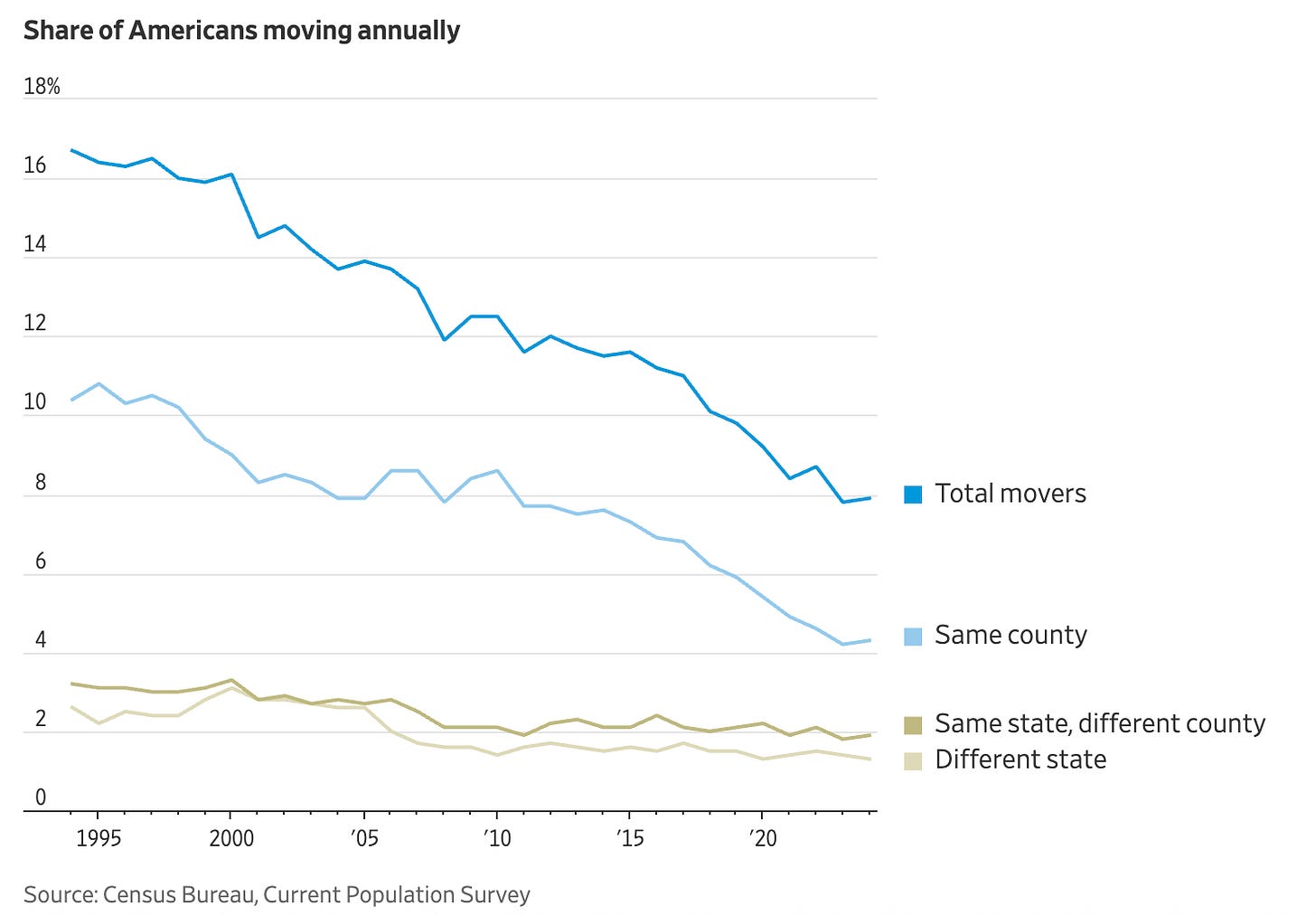

The current economic environment and high housing costs, particularly in larger urban areas in the Northeast and California, could be contributing to the latest trends. But the issue runs deeper, and longer, than just the most current years. Here’s the key graph from the WSJ piece. As you can see, the share of Americans who move in a given year has roughly fallen in half from 1995 to 2025.

We are now scraping historical lows, and mobility rates have declined across different demographic groups but especially among people in their 20s and 30s.

This lack of mobility is bad for economic dynamism. In the olden days a nurse or janitor might move to opportunity to get higher wages in the big city. Today, the big cities do pay higher salaries, but housing costs have risen so fast that a move is often not worth it financially. Teachers and other middle class workers are being priced out of the most expensive areas.

I’ve seen lots of discourse about how these mobility and cost-of-living issues are harming our economy, but I haven’t seen much talk about this trend in the context of K12 schools. Historically, parents would move to opportunity both in hopes of improving their own career prospects and to find better schools for their children. But if fewer parents can afford to move, that closes off pathways for kids as well.

Fortunately, it’s much easier for politicians to expand options within the K-12 space than it is to bring down the cost of housing. Politicians don’t control the housing market, whereas they do have some important levers over schooling. For instance, they could expand open enrollment programs and listen to parent demand by expanding over-subscribed charter schools and magnet schools. The Reason Foundation has found that public school open enrollment programs have seen large increases in demand, even in rural areas and from low-income students and students with disabilities, and that those students who transfer end up in better schools. In a separate report, Reason lays out how states can improve their open enrollment laws.

To put it in colloquial terms, an “abundance for education” platform would help relieve more families from feeling like their kids are stuck in schools that aren’t working for them.

Red versus Blue

At The Shanker Institute, Matt DiCarlo finds that, “the gap between higher- and lower-spending states is considerably larger now than it was 15-20 years ago.” I noted this trend last year and looked into how Red states and Blue states have been following very different education models. The Blue team is spending more, while the Red team is more focused on results. Mike Petrilli has been beating this drum as well, noting that Red states have been frontrunners on policies relating to the science of reading, charter schools, and school accountability systems. That work earned a New York Times shout-out this week from David Brooks.

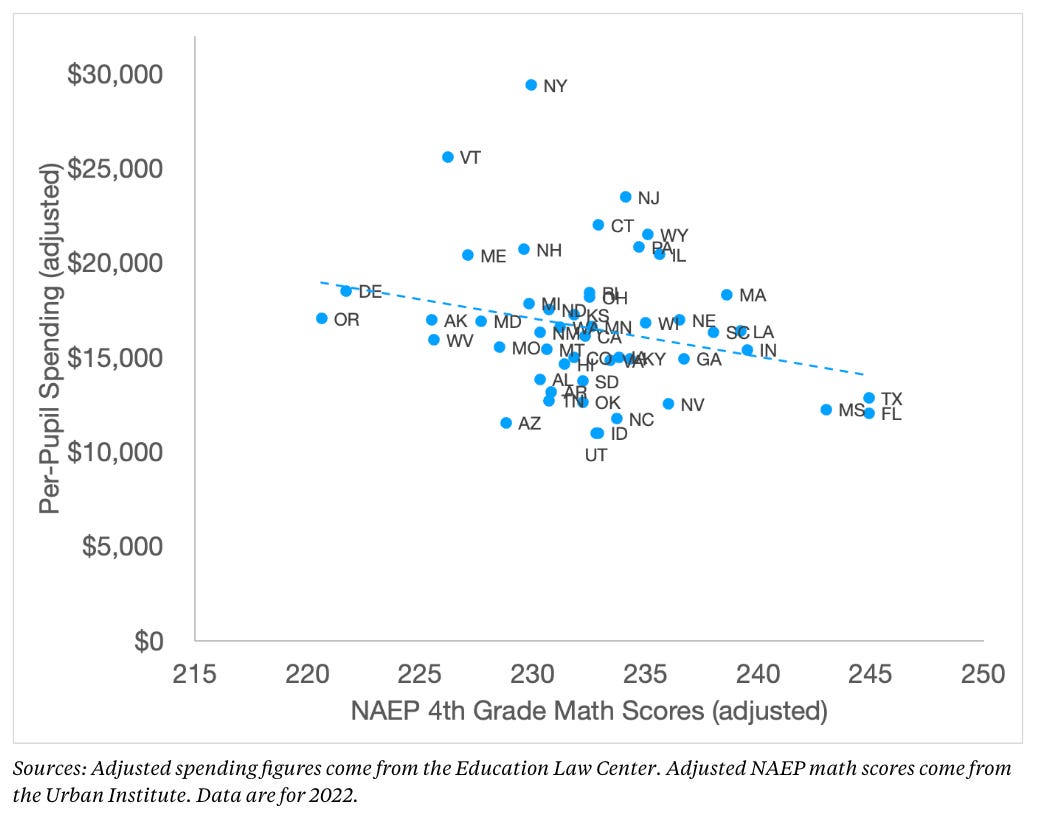

You can also see this in the data. Writing in The 74 last month, I noted that Blue states are the higher-spending ones, but they’re not getting better outcomes. New York, Vermont, New Jersey and Connecticut are getting pretty mediocre results given their investments.

On the other end, lower-spending Red states like Mississippi, Texas, and Florida are getting better student outcomes at a much lower cost.

My takeaway: Some places, especially the Mountain West, would probably see real gains from higher spending. Meanwhile, other places, especially in the Northeast, could benefit from more time thinking about cost effectiveness and how to drive improvements without additional funds.

Odds and ends

I’ve been a fan of the “just give poor people more money” treatment for poverty. And the evidence so far here in the U.S. has not found any negative employment effects of universal basic income (UBI) experiments. That is, receiving payments has not induced people to stop working. Still, in The Argument, Kelsey Piper surveys a recent wave of new studies and can’t help but conclude that, “guaranteed income transfers do not appear to produce sustained improvements in mental health, stress levels, physical health, child development outcomes or employment.”

Teachers really do not like the “equitable grading” fad. One teacher commented that, “Equity grading is not leveling the playing field… It is simply lowering standards so that school districts look like they are meeting kids where they are, when in fact they are hiding their failures behind ‘equitable’ policies.”

For example, did you know that Jane Jacobs, the author who wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, was herself a gentrifier before she fought against any further gentrification? I didn’t before reading Applebaum’s book.