A (Real) Future of Learning

Articulating a vision for the future of public education

Reading List

Are teachers taking on second jobs—and is it causing burnout and turnover?

Listen to me, Jim Wyckoff, and Nat Malkus discuss “Why are test scores falling?”

Illiteracy is a policy choice, by Kelsey Piper

Why replacing radiologists with AI is harder than it seems

How good are microschools? We don’t really know

Asbury Park school district boosted graduation rates without increasing student achievement ($)

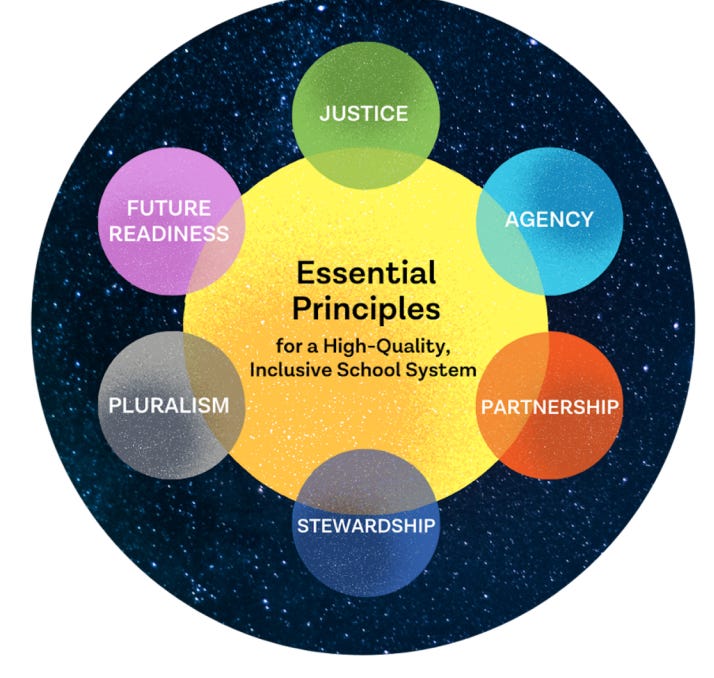

I got an email last week from The National Education Policy Center (NEPC), which describes itself as “a university research center housed at the University of Colorado Boulder School of Education” that “sponsors research, produces policy briefs, and publishes expert third-party reviews of think tank reports.” The email announced an exciting new “Blueprint for Public Education” from a group called “The Future of Learning.”

I was intrigued. I think we need a lot more smart thinking about the future of education in this country, so I was eager to dive in. The group is funded by some big names in philanthropy, and they have offices in midtown Manhattan, so they should have some firepower to bear on the pressing problems facing public education in this country.

And yet, I was severely disappointed. For one, the “Future of Learning” vision document did not include the words “reading” or “literacy” or “math” or “science” or “history.” It also didn’t include the words “college” or “career.”

In fact, it wasn’t really much of a “learning” agenda at all. As far as I can tell, it’s basically just a position statement against what it calls, “efforts to dismantle and privatize public education.” But it doesn’t offer its own competing vision for what that should actually entail or how things should change.

We can do better than this

A recent PPI “compact” for educational excellence offers a more compelling blueprint that, “refocuses public schools on their core academic mission, ends the retreat from rigor and merit, increases opportunity for learners of all backgrounds, expands parental choice of public schools, closes achievement gaps, and moves to a post-bureaucratic system of autonomous and accountable public schools designed for today’s children.”

Now that’s a vision that means something and which I can get behind. So how do we get there? The authors articulate nine components:

A goal of universal literacy by fourth grade; numeracy by eighth grade; and reading and math skills by graduation that enable students to succeed beyond high school.

A larger voice for parents in school policies and decisions.

A high-quality early childhood education program for every family that seeks one.

A bridge from K-12 to adulthood.

An expansion of public school choice and school autonomy.

An unwavering commitment to accountability for all schools that receive public dollars.

A new model for the teaching profession.

A strong but targeted national role.

A civic education that teaches our children what it means to be an American.

In their conclusion, they note that, “the political left is stuck defending a system that too many families no longer believe in.” (See first section above.) But, “the door is open — for a new narrative, vision, and generation of reform leadership.” I couldn’t agree more, and the PPI vision is a very solid start.

The Future of Learning statement reminds me of these Profile of a Graduate that states are adopting with all of these vague, unmeasurable platitudes (e.g., New York's has "critical thinker, innovative problem solver, literate across content areas, culturally competent, social-emotionally competent, an effective communicator, and a global citizen").

Chad, thanks for sharing this. I see 'future of learning' stuff daily, but had missed this one.

One small, but essential point: 'Universal literacy by 4th grade' should be, at the earliest, by fifth grade. (Sixth is more practical for reaching 99%.)

The best fifth grade classrooms I know are still giving systematic, explicit instruction in the types of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax needed to process school-level text.

(Those classrooms are considered far ahead of the pack. I certainly know of no one advocating for moving that instruction back into 4th grade.)

Thus, 'universal literacy by 4th' sends the signal that the critical, explicit instruction done in the 5th grade is not essential to literacy. A signal that should not be sent.