Surveys are not real life

Issue polls may be misleading you

In 2022, Education Next surveyed 3,641 Americans about whether funding for public schools in their community should increase, decrease, or stay about the same. 59% said increase.

But when told how much their local school district actually spent, support for increasing funding fell to 48%.

In 2021, they asked whether teacher salaries should increase, decrease, or stay the same. 67% said increase. But when given the average teacher salary in their state, only 53% said increase.

This is kind of remarkable when you stop and think about it. People give different answers when they get just a tiny bit more information. They’re getting this information on the telephone… from a stranger… and that’s still enough to change the results.

So what about in the real world? In the NY Times, German Lopez looks at the disconnect between issue polls and actual votes on a range of issues. He cites several examples, but I’ll pull out two:

Universal gun background checks had 87% approval in polling, and yet when put on the ballot box they’ve only garnered between 48 and 59% of the vote, depending on the state and year.

When asked in a poll, 82% of respondents said they supported housing rent controls. But when given a chance to vote on such a policy, only 40% of Californians approved.

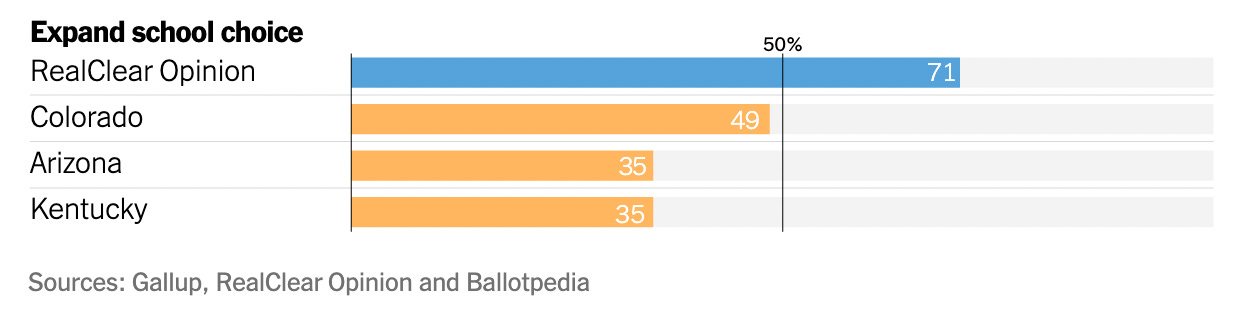

And what about in education? Lopez points to the contrast between the issue polling around school choice versus what happens when it actually goes on the ballot. Based on his preferred survey numbers, 71% support expanding school choice. Meanwhile, school choice referenda actually failed on recent ballot initiatives in Colorado, Arizona, and Kentucky.

On school choice specifically, EdNext published a great piece earlier this year from Parker Baxter, Michael Hartney, and Vladimir Kogan unpacking the school choice results. They looked closely at the failed 2024 campaigns as well as the history of the (losing) campaigns going back to the first one in Michigan in 1978. They write:

Not a single measure was successful, regardless of whether it focused narrowly on private school vouchers or included other reforms such as public-school open enrollment (e.g., Oregon in 1990). Voters rejected proposals for policy change brought forward using the initiative process but also repealed laws that had already been passed by conservative state legislatures (e.g., Utah in 2017 and Arizona in 2018). They said no to universal programs open to all students and rejected narrower offerings targeting specific populations.

They note that five out of six referenda attempting to expand charter schools also failed at the ballot box.

So what’s going on here? What explains the disconnect between what voters say they want versus what they’re actually willing to vote for? Lopez points to a number of factors, including the fact that the specific wording on poll questions often differs from how it appears on ballots, and wording matters enormously. But it could also just be a difference between how things sound in theory versus how they may actually play out on the ground.

Ultimately, I think the best explanation is to try to understand human behavior. If someone asks you on the phone whether you would support school choice, you might think in the abstract. Do you like the idea of school choice? Or, if you’re a parent, you might even think in practical terms of finding a better school for your child.

But when voters get into the ballot box, they might take a different mindset. They’re thinking about what might happen to their local school or to their property values. As Baxter, Hartney, and Kogan write, voters, “are likely to evaluate choice proposals primarily through their expected (or feared) impact on their local public schools.”

Once you understand this disconnect, it helps to explain the latest wave of school choice reforms. It explains why school choice referenda have failed in Red states like Kentucky and purple states like Arizona and Colorado. It also explains why Republican Governor Greg Abbott had to spend so much political capital to pass an education savings account bill in the Republican stronghold of Texas. Despite the high polling numbers, support from rural Republicans just wasn’t there until Abbott strong-armed his party into going along.

And, when parents are given a choice, they often like it. The numbers of families taking up school choice options in states like Florida and North Carolina are simply amazing. This all perfectly fits with the polling-versus-voters disconnect.

I don’t have a smart final takeaway here except to urge you to be a little more skeptical about any poll that suggests people are wildly in favor (or wildly opposed) to your favorite policy ideas. Even when the polls are behind you, just because nothing is happening on your preferred issues doesn’t mean that all politicians are stupid or corrupt. The reality on the ground is often much more complicated than an issue poll makes them out to be, and it takes leadership and (gasp!) maybe even bipartisanship to actually get things done.

Reading List

These Schools Are Beating the Odds in Teaching Kids to Read

The Leaky Pipeline: What happened to Ohio’s high-achieving low-income students?

Most polls are slipshod, creating a “stratified random sample,” is costly and time consuming, with intended or unintended bias …however polls attract eyes to screens … all that matters

I do wonder if there isn't something that the campaigns/messengers can learn/adopt here. If voters, as you write, are getting to the ballot box with a different mindset, then maybe the messaging prior to that point wasn't effectively addressing their concerns/values.