Pension plans aren't governed by angels

They're governed by politicians

When I first started writing about teacher pensions 15 years ago, I got into a debate with a family member over whether teacher pensions were “sustainable” or not.

At the time I argued yes. I remember arguing that if pension plans took a reasonable amount of risk and shared that risk across employees, employers, and retirees, then it was possible for the math to work out on defined benefit pension plans.

It took me a while, but over time I realized that pension plans are not governed by angels; they’re governed by human politicians. And because of that, they take on an unreasonable amount of risk and they pass that risk onto future teachers and taxpayers.

In a series for Bellwether Education, I look at the consequences of these human decisions:

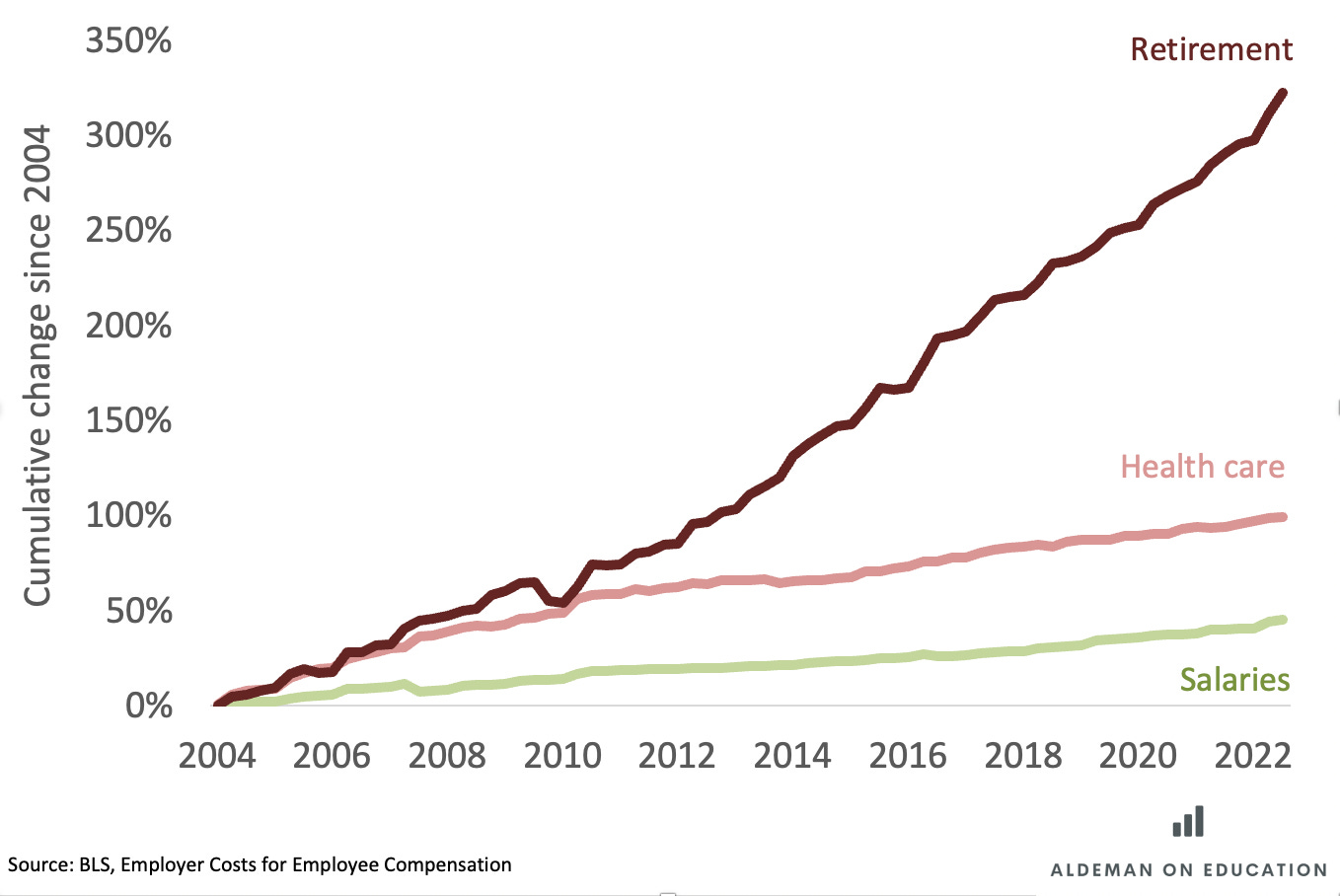

In Part 1 I look at the escalating costs of teacher pension plans nationally. I show that rising pension costs are a key reason behind stagnant teacher pay. Worse, the increase in pension costs is all coming from growing “pension debts,” aka the money that should have been put into the plans in the past but isn’t there to fund the pension payments that politicians have promised.

In Part 2 I break down those costs at the district level for the 100 largest school districts in the country. It may be hard to mentally translate $800 billion in pension debt into meaningful terms, so I show how those costs work out on a per-employee and per-pupil basis. On average across the biggest districts, pension debt costs are eating up the equivalent amount that it would cost to provide small group tutoring to all students.

Part 3 looks at retirement numbers across the 10 largest teacher pension plans. Like a lot of people, I worried that COVID-19 would lead to a massive wave of early retirements. But there is no evidence of that. Instead, the retirement rates from “teacher” pension plans look about the same as they did before the pandemic.

So, are teacher pension plans sustainable? In Part 4 I look at what the future might hold for teacher pension plans. Thanks to declining student enrollments, the plans are at risk of having to increase their contribution rates, cut benefits for new workers, or some combination of both. In other words, a continuation of the trends of the last 20 years….

At the end, I wrap up the series by outlining four principles for state leaders to responsibly pay down their pension debts. It is still possible for policymakers to ensure that money intended for schools makes it into classrooms, but that will require them to act.