"No One Wants to Be A _______"

The continued decline of the humanities, and how it affects education

Reading List

ChatGPT and the end of learning by Lakshya Jain

Schools are all about imparting “skills”—but what about actual knowledge? by David Steiner

Murder rates are on track to hit new modern lows, notes Jeff Asher

What progressives should be thinking about Social Security reform by Andrew Biggs

Preston Cooper finds that college enrollment is down, but only for “bad” colleges

Parents, LAUSD settle lawsuit: 100,000 students to get tutoring for three years

A 1st grade teacher told this parent to stop reading to her child

In the world of education, I often hear that, “no one wants to be a teacher anymore.” That’s not literally true, given that schools are employing more teachers than ever.

Maybe people who say things like this are really just talking about vibes more than data. Here I get a little prickly: While fewer college students are majoring in education through traditional preparation programs, faster and cheaper alternative routes into the teaching profession have been booming.

How should we think about this? On one level it’s important to step back and ask how education compares to other college programs. After all, education is susceptible to the same societal trends that every other major is subject to. In that context, you see that college students have been flocking to higher-paying majors like the hard sciences and computer science. Even nursing has done pretty well, perhaps because nurses are getting paid more than they used to while teachers are not.

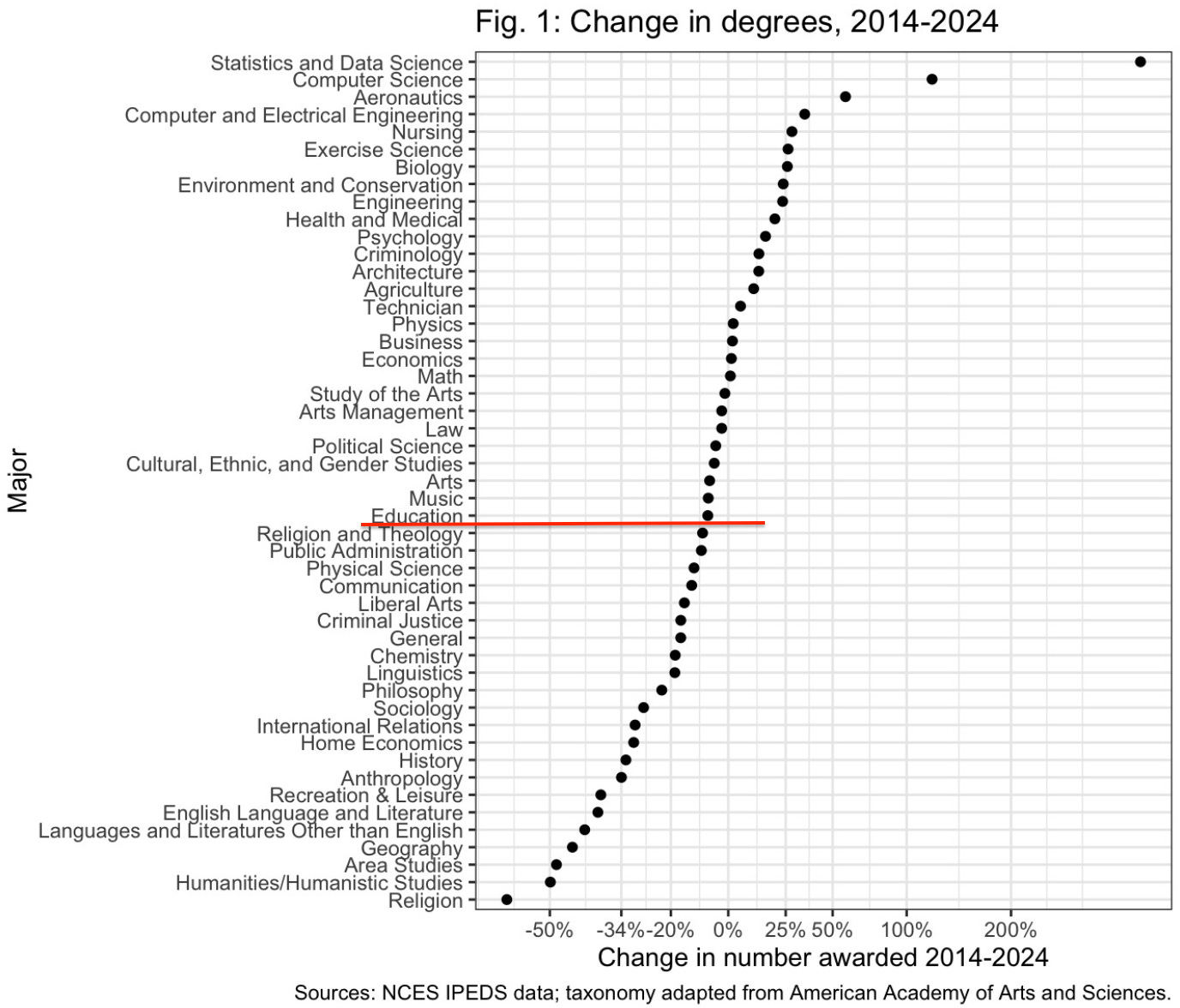

And when you zoom out like that, you can see that teaching looks pretty similar to other liberal arts majors. Over on Bsky, Ben Schmidt crunched the numbers on the change in bachelor’s degrees over time. I added a red line to his chart to highlight education. It falls right between music and religion/theology, and it’s suffered a smaller decline than communications, philosophy, sociology, and other humanities programs.

This should make us feel a bit better. It’s not literally true that schools don’t have teachers, and education as an occupation doesn’t look any worse off than other liberal arts.

But where are schools getting their teachers, if not for traditional preparation programs? Many of them have turned to the aforementioned alternative route programs. That must be a bad thing, right? Not so fast…

In the most extreme example, Texas opened the door two decades ago to online, for-profit alternative licensure programs that did not require teachers to have any student teaching or classroom experience prior to teaching. Many people in my orbit were appalled at this idea. They pointed to advertising slogans the companies used to attract recruits. One billboard at the time read, “Want to teach? When can you start?” and implied that anyone could become a teacher without much need for training. This type of message offended many of my policy friends.

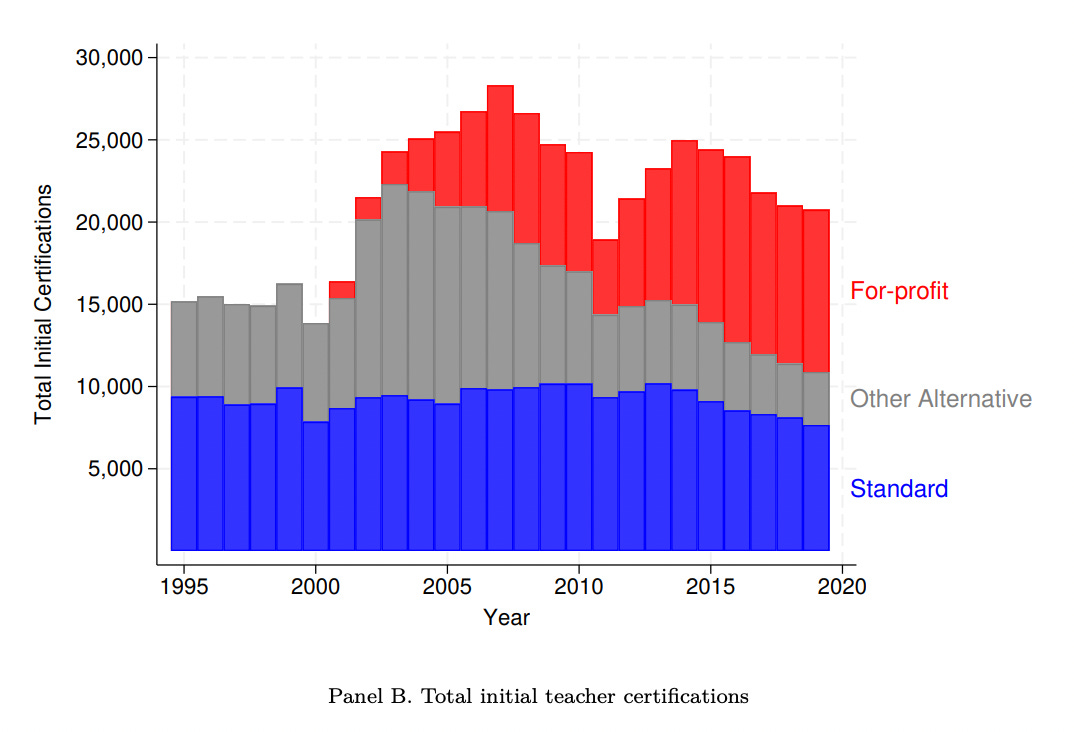

But a new NBER paper by Christa Deneault and Evan Riehl looks at what happened in Texas. First, as the chart below shows, the new for-profits ate up an increasing market share of new teacher certifications. The share of all Texas teachers with for-profit certifications grew from 0 to almost 20 percent.

Two, they found that the teachers coming through the for-profit pathways did have higher turnover rates and were (slightly) less effective at raising math and reading scores than teachers who came through standard preparation programs.

That sounds bad! Most people would stop there, but Deneault and Riehl consider the counter-factual. That is, if Texas schools were unable to hire teachers from the for-profits, who would have filled those classrooms?

Here’s where it gets interesting. After the for-profit programs opened their doors, the number of teachers without any license at all dropped from five percent to one percent. That is, the for-profits boosted supply and provided a valid alternative to… essentially nothing. And, while the teachers trained by the for-profit colleges were slightly worse than the teachers coming through traditional preparation programs, the for-profit trainees were quite a bit better than teachers who were unlicensed and had no training at all. On net, Texas’ experiment with reducing teacher training requirements neither raised nor lowered student achievement, even in schools that hired more teachers coming from the for-profits. From the student’s perspective, it was basically a wash.

Deneault and Riehl also found no significant effects of the Texas policy on the number of employed teachers overall or on average teacher wages. But they did note that the policy affected which people got into teaching, and that the for-profit programs boosted the state’s supply of Black and male teachers.

And here’s the kicker: The for-profit programs were significantly shorter and cheaper than the standard routes. After considering all these potential impacts, Deneault and Riehl conclude that, “the main effect of the Texas policy for teachers was a reduction in the time and monetary costs of training.”

The Texas story illustrates some real trade-offs around barriers to entry into the teaching profession. I don’t think the lesson here is that state policymakers should just give anyone a license, and I personally like the apprenticeship model that more places are trying out, which puts prospective teachers into classrooms right away and doesn’t require them to pay thousands of dollars in tuition upfront. Teacher leadership teams could do an even better job of easing the transition process from candidate to full license.

But I do think we need more humility around these questions. In Texas, faster and cheaper preparation programs did not necessarily hurt student outcomes, but they definitely helped schools find teachers, and they allowed people who didn’t have the time or money to invest in the years of training required by a traditional preparation route to still find a way into the classroom.