How slow is too slow?

A new book argues reading instruction is failing to challenge kids

Tim Shanahan is one of my favorite reading researchers. His blog explains the research on how kids learn to read and translates it into what it means for schools and teachers. I read a lot of his old posts as I was creating Read Not Guess, and his work continue to inform how I build out the program.

So when I saw Shanahan had a new book out, I jumped at a chance to read it. In Leveled Reading, Leveled Lives, he offers a forceful argument that many schools are getting reading instruction wrong. He cites data showing that kids should be taught to read using challenging, grade-level texts, rather than the “instructional level” texts that are more commonly used.

I have a more traditional book review up at The 74. I recommend reading that first, or the full book is available for purchase here.

But I’m using this space to walk through a mental model that helped me understand his arguments. Namely, Shanahan devotes his first chapter to the evolution of the materials used to teach kids to read and how those have gotten progressively easier over time. In fact, Shanahan argues that kids are now being taught to read using books that are far too easy for them, which effectively traps them on a “treadmill with no exit.”

What does he mean by this? As I read through it, it helped me understand it better when I visualized it. I’m doing my best to share that here today. So the condensed history below is cribbed from Dr. Shanahan’s book, but the bad drawings and the crude storytelling are entirely mine. Please forgive my artistic license, and do not blame Dr. Shanahan for what I’m about to show you! Any errors are my own.

With that caveat out of the way, let’s start at the beginning. In the 1600s and early 1700s, most people didn’t learn to read at all. A rare chosen few were taught how to read, and the most popular book they used was the Bible. In fact, some people at the time wanted to learn to read so that they could read the Bible. It was (and likely remains) the most common book in American homes, and it was frequently used for reading instruction.

But the Bible is hard to read. When I was a kid, I thought it would be a fun challenge to try to read the whole thing cover to cover. I think I got to page 11 before giving up. Nowadays, there are programs you can follow to cover the full book in one year, but even that is a serious commitment. The point is, it would be a hard book with which to learn to read. Back in that era, it was an immediate and steep climb to go from not reading to reading.

Over time, things got easier.

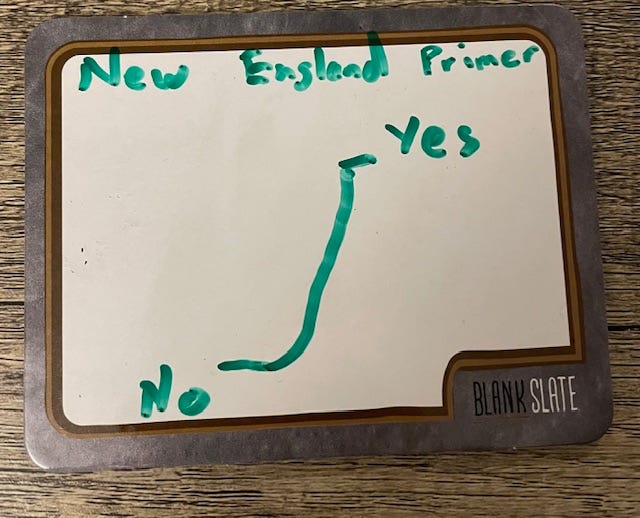

The first evolution was the New England Primer, which offered reading instruction over 90 pages. It sold millions of copies and started with the alphabet and nursery rhymes, lists of vowels and syllables, simple short texts, and then eventually turned to more complex text.

In picture form, think of this like a pretty fast journey. It started with the basics and had a runway, but the content and material advanced quickly. More importantly for our purposes, it was all contained in one book.

Next was the Noah Webster era. This is the first time that reading instruction started using multiple books. The first book in the series emphasized the ABCs and letter sounds, along with lists of two, three, and four syllable words covering a variety of spelling patterns. The second book was about grammar (according to Shanahan it didn’t sell well), and the third featured a variety of important speeches and other texts.

For our purposes here, it was still a quick evolution to go from not reading to reading, but the books were no longer self-contained. Now there were three.

Starting with the “common school” movement in Massachusetts, the states began offering public education to a wider group of children. To handle this influx of children, schools started assigning kids to grade levels based on their age. Shanahan writes that, “The graded textbook programs represented the first true realization of the notion that reading could be taught successfully by leading students through a sequential series of texts gradually increasing in difficulty.”

The most popular of these books were the McGuffey Readers. Instead of using one book to learn to read, now there were seven. (As an added bonus, the textbook publishers discovered they could make more money by selling six or seven books to a school rather than just one or two!)

Over time, schools started looking around for even more differentiation. After all, grade levels were more fine-grained than the old primers and readers were, but individual students could still be above or below grade level. Besides, many schools were now being asked to educate the masses and teachers often had to deal with class sizes of 40 or more students.

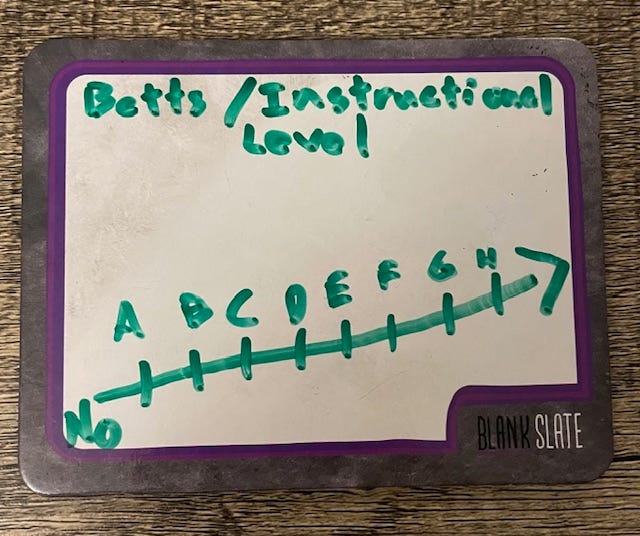

Psychologists also began testing students to see how much they could read and understand. In 1946, a researcher named Emmett Betts recommended that a text would be beneficial for instruction if students could read the words with 95 to 98 percent accuracy and 75 to 89 percent comprehension of the text. In other words, he was trying to find a threshold for when a text was “just right” for a child. There have been various debates over the years about what exactly is the “right” threshold, but all of those proposed thresholds are quite high.

More importantly, this idea has carried over into the modern moment. Shanahan estimates that the majority of American children are being taught using these sorts of “instructional-level” texts, as opposed to truly “grade-level” ones. Most (in)famously, the Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System sorts kids and books into an A-Z continuum. The result is a very slow progression that may or may not end in grade-level reading success.

This may seem like a nice, neat progression, but there are several flaws with the idea. For one, it has proven impossible to accurately identify where a kid is. Who is a “C” and who is a “D?” It will matter based on the day and the content of the books. As a young kid, I would have done very well on any text about Iowa Hawkeye football—I had all the players names and numbers memorized—but I knew next to nothing about soccer or hockey or gymnastics.

Even beyond the measurement issue, which is significant, this type of leveling means that reading instruction advances so slowly and so gradually that many kids never learn to read grade-level content. The end result is what I wrote about back in October: Less than half of kindergartners who are off track catch up by third grade, and their odds get lower and lower every year they remain behind. Meanwhile, parents aren’t given clear answers and mistakenly believe their child is performing at grade level even when they are not.

Shanahan argues—persuasively—that kids deserve the chance to be able to rise to meet grade-level standards rather than being stuck in these easy texts. For more on why this debate matters and how it could change instruction and student motivation, read my full review at The 74 or buy Shanahan’s book here.

Reading List

Aldeman: What Can States Do to Help Students Learn More Math?

David Epstein on what London taxi drivers can teach us about AI

“Some kids are just dumb” is not good education policy by Kelsey Piper

Why ChatGPT for Teachers Might Make Things Worse by Carl Hendrick

Megan McArdle: The signs of educational decline are now impossible to ignore

Do Kids Really Stop Learning to Read and Start Reading to Learn After Third Grade?

State Reading Laws Focus on K-3. What About Older Students Who Struggle? ( EdWeek)

Miah Daugherty on Addressing the Middle School Reading Crisis

Long piece by Nathaniel Hansford: How to Support Struggling Readers in Grades 4 and Up?

Chad—what are your thoughts on the role of teaching explicit grammar in the progression of literacy instruction? I went to a French school until I was 9, where grammar was a huge part of what we learned—a lot of repeating verb endings and dictations, for example. Because French grammar is so hard, it is impossible to learn to write French without explicitly understanding grammatical rules, but that becomes a huge help later on as readers progress. Ironically Americans don't really teach grammar explicitly because English grammar is by comparison quite simple (namely verb conjugation). I think that hinders later reading instruction. Curious if there is research on this? I don't often see it discussed.

Grade level is misleading, too. What a child learns in grade 1 can not compare to what a child learns in grade 4 in reading. There is much more packed into the first three grades than in later grades. There are problems with a highly structured reading scope and sequence. The language that is needed to be consistent with the scope and sequence is not what children hear or speak. Nat the fat cat sat on the mat is excellent for teaching short closed syllable words, but not for communicating with others. I dislike the controlled vocabulary books. They do not expand vocabulary, nor do they have any interest for students who are reading below their maturity level. Read real literature, but provide the scaffolding and help with vocabulary. It is slower than reading dumbed-down text. But the gains are significant. This contradicts Engelmann and Carine's rule to have teachers talk less and have high rates of student responses to simple questions. "What word?"