Is teacher turnover *too low*?

Let's poke under the conventional wisdom

I have a new piece out at The 74 this week taking a look at the latest teacher turnover numbers. Despite what you may have heard, teacher turnover rates appear to be trending downward. Here’s the key chart:

The data come from a range of state dashboards and research reports, and they all paint a pretty similar picture: Turnover rates fell in the fall of 2020, when the economy was in rough shape and schools were mostly still closed. Then they started to tick up in 2021 and especially in 2022. But then they started to fall—they were mostly down in 2023 and down again in the states where we have data on what happened in the fall of 2024.

In other words, the COVID spike did not lead to any sort of permanent damage to the teaching profession, and turnover rates appear to be settling back to where they were pre-pandemic. As I noted in The 74, the long-term teacher turnover rates have stayed within a relatively narrow band for a very long time:

Dan Goldhaber and Roddy Theobald looked at teacher turnover rates in Washington state from 1984-85 to 2021-22 and found that total turnover, including teachers who left the profession, switched schools, or left teaching but stayed in education, has ranged from about 14% to 20% in Washington since the mid-1980s. It did indeed hit a modern peak (of 19.8%) in 2021-22, but Goldhaber and Theobald’s more recent work in Washington showed turnover was again starting to fall in 2023.

I also note that turnover rates in public education are lower than they are in other industries, and that classroom teachers tend to have the lowest turnover rates within public education (much lower than classroom aides or other service employees like cafeteria workers or bus drivers).

Is teacher turnover too low?

I actually think it’s worth asking whether teacher turnover is too low. That’s crazy talk, I know, but hear me out.

First, let me acknowledge the counter argument. It is true that teachers improve on the job, especially in their first few years. There’s some debate in the research community about just how long and how fast they improve and if they ever hit a plateau or not, but it’s fair to say that veteran teachers tend to outperform novices.

It’s also true that the supply of new teachers is lower than it was 20 years ago, especially coming from traditional preparation programs. So if a school loses a teacher now they would have a harder time filling that role than they would have when supply was higher. Still, schools today employ more teachers than ever, so they are willing to hire people even as they complain about having fewer options.

These things are all true. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that school leaders or policymakers should strive to boost teacher retention rates at all costs.

One reason is that, while teachers do tend to improve, they don’t improve at the same rates. A couple research studies have found that teachers who perform well in their first few years on the job tend to improve faster than those who initially struggle. First impressions matter, and districts should be acting much more aggressively on that early information.

There’s another common misconception here. It is, in fact, not true that schools lose their best teachers; the opposite, in fact. Teachers who leave the profession tend to be worse than those who stay. You can see it in this straightforward graph from BESTNC on the North Carolina workforce. It divides up teachers who stay in North Carolina schools (in blue) versus those who leave (in orange). At every experience level, the teachers who stay produce higher student growth rates than those who leave.

This graph happens to use data from 2022-23, the worst year of the pandemic, and it still shows that schools held onto their best teachers and lost their least effective ones. For what it’s worth, BESTNC has replicated this graph for a number of years in their Facts & Figures: Education in North Carolina reports.

What we’re seeing in the North Carolina data could be driven by a combination of teacher preferences and districts nudging out their lowest-performers. But the evidence suggests districts aren’t very picky. They generally don’t fire or lay off many people, they don’t even evaluate all teachers annually, and those evaluations tend to be formulaic and result in overly inflated ratings.

But what about districts that take their employer roles more seriously? Districts that are more aggressive about selective retention could potentially improve the quality of their overall workforce.

In one paper, Laura Sartain and Matthew Steinberg looked at the effects of a teacher evaluation reform in Chicago. They find that, “the reform increased the exit rate of low-rated tenured teachers by 50 percent. At the same time, the teachers who replaced the exited teachers were significantly higher-performing.”

They also conducted a modeling exercise to see what would have happened if Chicago had used higher performance thresholds under their REACH evaluation system. The city actually used a threshold of 210 points to identify a teacher as “Unsatisfactory,” but what if they had set a higher threshold? In the graphs below, a value of 0 indicates that a new teacher would have performed the same as the low-performing teacher they replaced. I drew the red lines to help you see the outcomes. Even at the highest theoretical threshold, 96% of Chicago’s new hires would have outperformed the teachers they replaced (that is, most of the distribution is to the right of the red line) on the REACH system. The numbers aren’t quite as high for value-added scores, but here too the new hires generally outperform the existing workers.

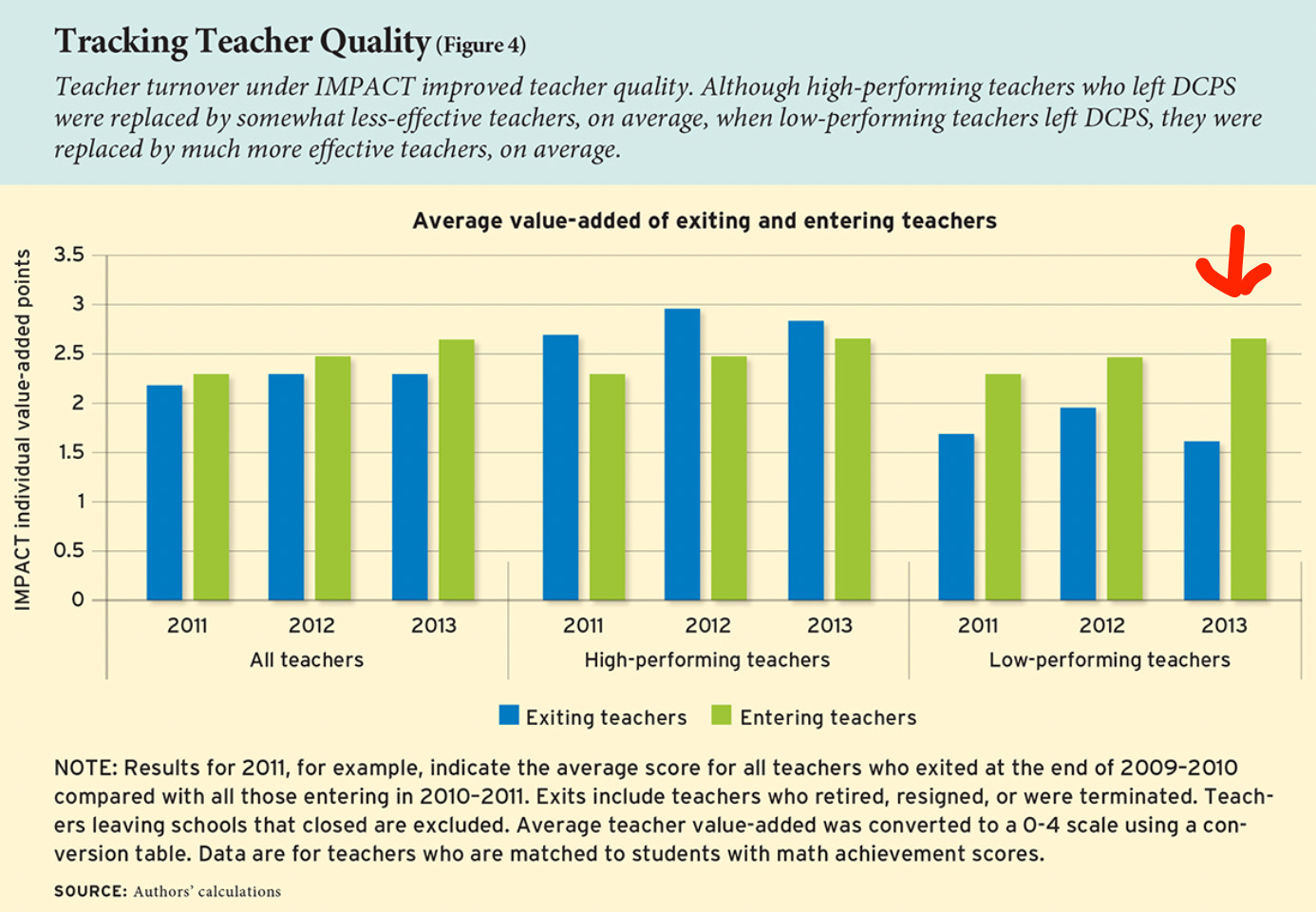

This Chicago paper is partly theoretical, but it’s played out in real life in Washington, D.C. Thomas Dee and James Wyckoff found that the district’s evaluation system nudged out low-performing teachers, and that their replacements performed better.

In fact, by practicing selective retention, the district kept the teachers it wanted to keep and pushed out those who weren’t performing that well. This cycle produced “consistently large gains” for students in high-poverty schools.

In other words, policymakers shouldn’t worship at the altar of boosting teacher retention rates at all costs. Students would probably learn more if schools were just a little bit more picky about which teachers they put in front of the class.

“In fact, by practicing selective retention, the district kept the teachers it wanted to keep and pushed out those who weren’t performing that well. This cycle produced “consistently large gains” for students in high-poverty schools.”

So many assumptions, do plumbers or accountants continue to improve or plateau? Are measures of teacher effectiveness based on test scores? Are the tests “valid and reliable” measurement? Do teachers move from lower achieving to higher achieving schools? Does teacher effectiveness correlate with teacher collaboration? How does school leadership impact teacher retention and teacher effectiveness? Do teacher preparation programs impact teacher effectiveness? If so, why?

The list is endless,