Are Teachers Underpaid or Overpaid?

A new paper suggests maybe it's both?

Are teachers underpaid or overpaid? That’s a surprisingly tough question to answer.

The Economic Policy Institute says that the “teacher wage gap” keeps hitting all-time highs. Last year, they reported that teachers made 27% less in weekly wages than other “similar” professionals.

But friends don’t let friends cite the EPI data uncritically. Why? Lots of reasons…

First, do you get paid in “weekly wages?” I don’t. Slightly more than half of all workers are paid an hourly wage. Their income is directly tied to how much they work. Other workers—including teachers—get an annual salary regardless of how much they work. Regardless, the use of “weekly wages” should be your first red flag that the EPI calculations are a little funny.

Second, who are “similar” workers to teachers? EPI uses, “standard regression techniques to control for systematic differences in age, education, state of residence, and other factors known to affect wage rates.” In practice, teachers are one of the most well-educated occupations in the country, meaning EPI is effectively comparing teacher salaries with those of dentists, physical therapists, pharmacists, and economists. In fact, using the same EPI methodology, Andrew Biggs has found that nurses and firefighters are dramatically overpaid. Why? Because, while EPI is assuming that all educational credentials are created equal, the market values different jobs and degrees differently, and teaching degrees are on the lower end.

But third, and most importantly, the EPI data don’t tell us what happens to actual teachers when they enter and exit the profession. If they are correct, and teachers are earning far less than they should, then teachers should see a huge pay increase when they leave the profession.

So, do teachers make more money when they leave? It turns out that, by and large, they do not. For example, a team of researchers led by Dan Goldhaber found that people who trained to be teachers in Washington state earned more money after they enter teaching and the vast majority earned less when they left. Matt Chingos and Marty West reported similar findings in Florida, although they found that teachers with higher value-added scores did have more career opportunities.

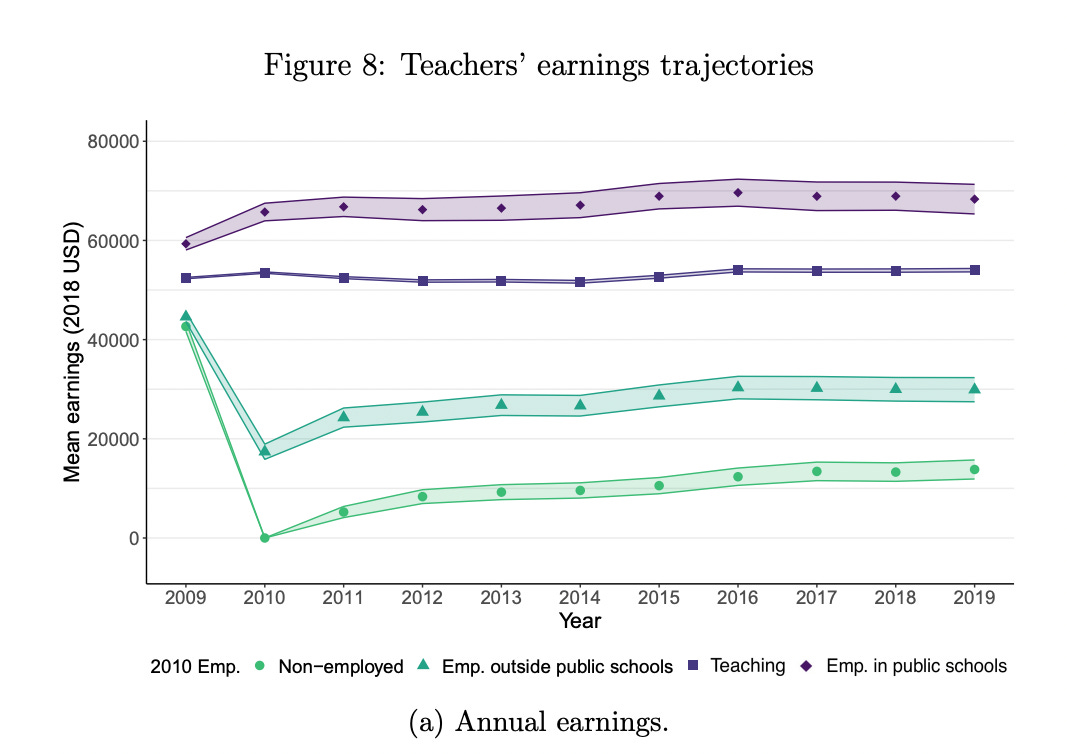

The latest piece of evidence on this front comes from a new working paper by Carolyn Tsao. Using Kentucky unemployment insurance data, Tsao followed people who left teaching in 2010 versus those who stayed as teachers. The chart below shows the results. The solid purple line in the middle of the graph shows the inflation-adjusted earnings trajectory of people who remain as teachers. It looks pretty flat. But now look at the two green lines, showing people who leave the field of education. The people who move to employment outside of teaching earn on average $21,000 less in their first year away from teaching and never recover their prior earnings levels.

As Tsao writes, “the only group that continually earns more than they would have as teachers are those who change to other public school employment; these individuals mostly move to administrative positions, which offer higher pay scales than teaching.” This is a pretty sad indictment that the only way for teachers in Kentucky to make more money is to get out of the classroom and into administration. This is indeed a sad state of affairs, and Kentucky policymakers could pursue other ways to make teaching more financially rewarding.

Tsao also looked at people who barely passed the Praxis licensing exam and estimated a passing score was worth $18,000-$21,000 per year. No matter how you look at it, it’s hard to look at the empirical data and conclude that Kentucky teachers are underpaid.

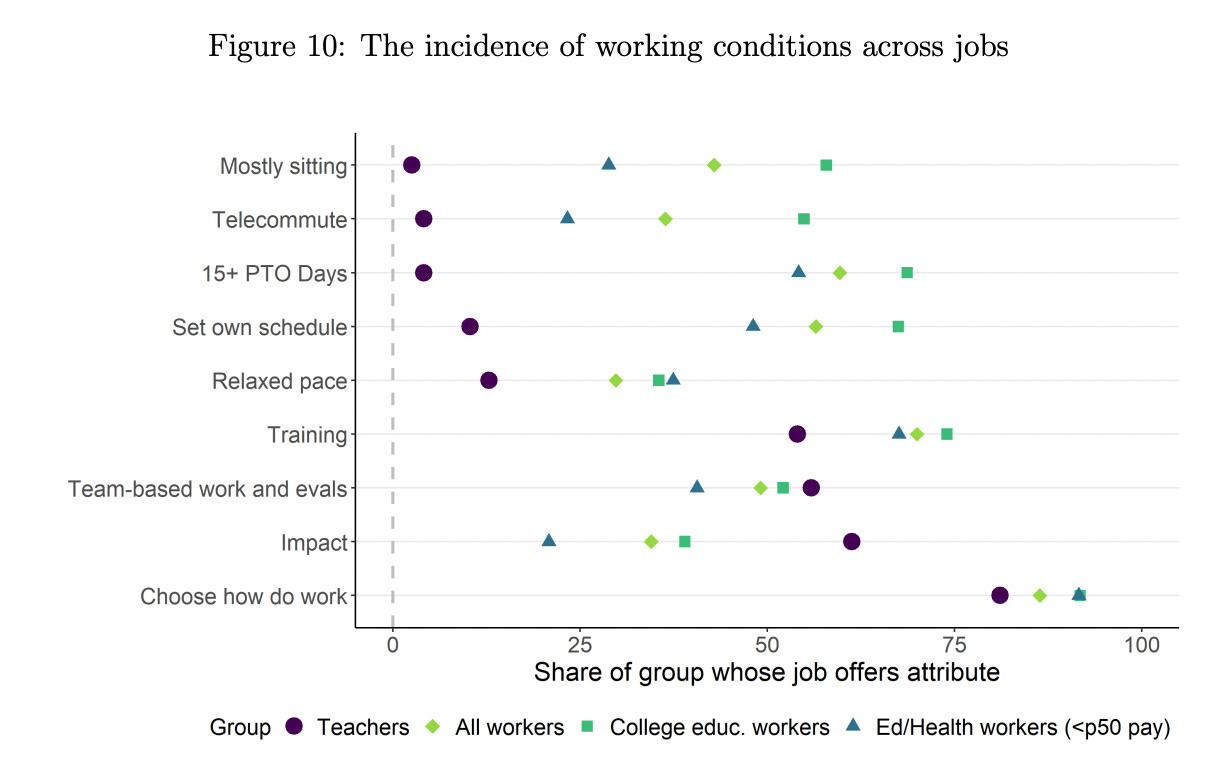

But wait. Tsao’s paper has another wrinkle to it. Notably, she documents that teachers tend to have tougher jobs than other well-educated, white collar professionals. They are more likely to be on their feet, have fewer opportunities to telecommute, and cannot set their own schedules. Teachers are also less likely to have “training opportunities to develop skills that will transfer to other jobs” and are more likely to report working alone. When Tsao presented hypothetical job offers to a representative sample of Kentucky teachers, she found that their “willingness to pay” for these features mostly accounts for the pay advantages to being a teacher.

In short, it’s possible that teachers are overpaid compared to market values but they’re underpaid compared to the demands of their job. This is a more complicated and nuanced finding than a simple yes or no, but it suggests there may be large benefits to improving teacher working conditions.

Reading List

North Carolina’s Advanced Teaching Roles program shows improved test scores

How Team-Based Teaching Can Support Student Learning and Reduce Teacher Burnout

Houston ISD is keeping its most effective teachers

AI is having trouble drawing chemical structures and the periodic table

Curious how pensions are counted. I suspect that teachers' cash wages are suppressed by the need for school districts to make large pension contributions, much of which is to pay for underfunding resulting from past undercontributing. The result would be that younger teachers are particularly underpaid on a total compensation basis, as the value of their future pension is less than the value of cash compensation that is effectively taken away to fund those pensions.

This was interesting, never thought about it like that.